Editor's Note: KwaTashea Marfo, one of the writers of this story, has an African American studies minor.

There was political unrest and several things needed to be addressed on Ball State’s campus. Fifty Black students were up for the test.

Sparked by the racial complications and the conditions of the 1960s, college campuses across the United States were in an uproar. African Americans were fueled with determination to change academic bureaucratic policies.

During the 1967-68 academic year, Ball State’s African American population faced two main concerns: the university’s lack of social activities for Black students and the need for representation of Black minorities in the curriculum and faculty. However, the demand for their issues were not met until a walkout was correctly timed.

On Feb. 8, 1968, President John R. Emens gave his televised farewell address, and two students in the middle of every row in Emens Auditorium stood up. The students walked out of the building in a quiet and orderly fashion, leaving the program disrupted with silence.

Fifty Black students walked out of Emens Auditorium that day, not focusing on disrespecting or humiliating the president but rather focusing on something bigger than Emens’ departure: injustices at Ball State.

The walkout was prompted after Ronald Payne, student and member of the Student Senate Judicial Board, was rejected by the School Senate to establish a committee to discuss racial discrimination on a social level a month prior. Payne was among the students in the walkout.

The Ball State Daily News’s Chris Inman reported on the walkout, saying “The [Black students] that walked out of Emens that night took a step, the first big step taken in the direction of recognizing racial problems at Ball State. Some people took notice, some turned their heads, some began to think and some closed their minds. Yet only time will determine the actual effects of this act and others which are rumored to follow.”

And change things, it did.

In the late ‘60s, Black studies was introduced as an institutionalized program at Ball State due to other schools fighting for African-American studies programs, such as San Francisco State and Cornell University, according to the film Agents of Change. While the program was introduced, the courses were not substantial. In an article by the Ball State Daily News from 1970, students said they were disappointed by the Black studies minor’s offerings, longing for the course structure to be expanded.

Furthermore, the program faced more delayed expansion when the professor who was teaching the program retired from Ball State in 2010, taking the minor with them. According to an article written for the Ball State Magazine, the minor was picked up by assistant professor Simon Balto, who joined Ball State’s history department in 2015 with a mission to relaunch the minor. In 2017, the program was launched under a different name: African-American studies (AFAM).

Balto departed from Ball State in 2018. Now, the AFAM program is led by director Kiesha Warren-Gordon, Ph.D., associate professor in the Department of Criminal Justice and Criminology, and assistant director Emily Ruth Rutter, Ph.D., assistant professor of English.

Jessica Reuther, assistant professor of history and African-American studies affiliate, said she believes the reason the minor was gone for so long was because no one had the desire to take on the task headstrong.

“Since then, luckily, we've seen the value and reinstated and redesigned it, really,” Reuther said. “Both Dr. Warren-Gordon and Rutter have really redesigned the program and made it, in my opinion, much stronger and more useful to students at the moment.”

Though the name of the minor is now African-American studies, Reuther said the course encompasses history and experiences of everyone affected by American history.

She said the units connect with students because they empower people of all marginalized groups, whether it’s race, economic status, sexual identity or something else.

“It shouldn't be placed on the Black faculty or students or other individuals of color to explain race to every white person on campus,” Reuther said. “And it's important that white students and white faculty educate themselves about these issues and can speak to issues of race knowledgeably, while also humbling themselves and understanding that no, I will never be Black, … but activism of all races is important.”

Initially, students could pick from nine disciplines — architecture, communication studies, English, history, political science, criminal justice and criminology, psychology, sociology and telecommunications — to pursue the minor. Now, the minor has designated requirements.

According to Ball State’s course catalog, students must receive 15 credits, nine of which are requirements of taking Introduction to African-American Studies (AFAM 100), African-American Studies Theory and Research Methods (AFAM 200) and African-American Studies Capstone (AFAM 400).

Students still possess the option to make the remaining credits tailored to their major with options in departments such as English, sociology or history. As of this year, the program has extended to the Honors College as a pathway in which Honors College students have the option to pursue the minor as part of the Honors requirements.

“I think that being able to work with students and provide students an opportunity to do work within and to learn about the Black community, the history of Blackness in the United States and within Muncie is important,” Warren-Gordon said. “Any opportunity I have to work with students, whether it's in African-American studies or in criminal justice, I want to be able to do that.”

Warren-Gordon said her interest in African-American studies came from her attendance at Ball State as a student who wanted to dive deeper into who she was.

“It's part of who I am, so wanting to know more about my history,” she said. “It's not just my history. It's part of the American story, right? So it’s our history, … how people who look like me helped shape this country that we live in today.”

Similarly, the passion and devotion expressed by Warren-Gordon is shared by John Anderson, director of the Ryan Family Navigators Program and faculty in the AFAM studies minor.

Anderson said the poem “I, Too” by Langston Hughes captures why the AFAM program is so valuable.

“I think the essence of [“I, Too”] is what I would want students who take any of the Black sociology or Intro to AFAM Studies [to know], … that they’re as much American as anybody else who claims to be in the United States of America,” Anderson said. “The way that we’ve come through to express our humanity and our Americanness is absolutely 100 percent important to be recognized, acknowledged and celebrated.”

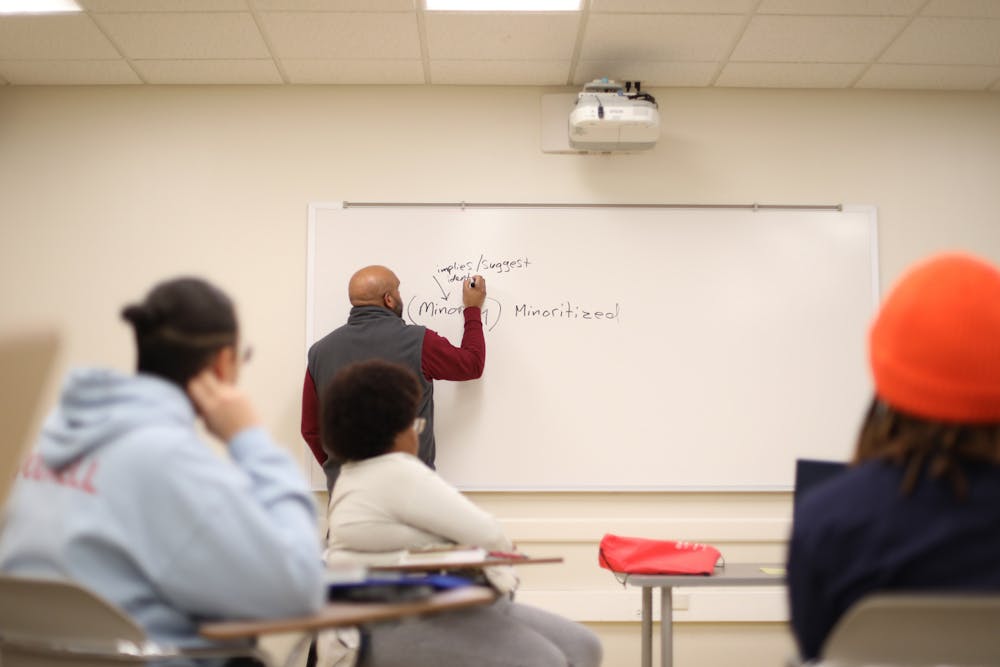

Per Ball State’s website, the AFAM minor is intended to instill students with critical thinking skills, intellectual dexterity, cultural competencies and knowledge of historical and modern contributions of African Americans to American life, culture and politics. This intent is a manner in which Anderson guides his class to “overwhelm students in a good way” about how Black experiences feed into American history.

Anderson achieves the opportunity by offering immersive learning aspects in his course curriculum as opposed to testing.

In AFAM 100 and SOC 221, Anderson takes his students on trips to Michigan to visit the Charles H. Wright Museum, the Motown Museum and the Jim Crow Museum. He tries to incorporate these museums into the trips, so students can “get deeper engagement” with the course material.

Anderson isn’t alone with this approach.

Previously offered in the fall, Warren-Gordon’s Black women and justice course was held at the Young Women’s Christian Association (YWCA), where students were able to work with the community and the people who lived there.

“It's not just about reading, it's about understanding and applying what they're reading,” she said.

As the AFAM program continues to broaden its horizons, there is hope that the program will someday establish itself as a major.

“The central aspect … I try to get students to think about in terms of the AFAM program is that the program aims to assist them to see history and [people of color] reflected at the university and their lives, even when they don’t feel valued in other courses sometimes,” Max Kantor-Felker, assistant professor of history and African-American studies affiliate, said. “Forty years from now, I hope individuals keep questioning the university, questioning how knowledge is produced to create a thriving, robust program that is more reflective and responsive just like history it was built on.”

The 50 students who walked out of Emens as an act of civil obedience laid the groundwork for one of the immersive academic programs on campus. Warren-Gordon said the AFAM program may become a combined department with women and gender studies to house the programs together to streamline resources.

Contact KwaTashea Marfo with comments at kwatashea.marfo@bsu.edu or on Twitter @mkwatashea. Contact Lila Fierek with comments at lkfierek@bsu.edu.