It was 1979.

Joaquín Vázquez of Arandas, Jalisco, Mexico, had just started living on the South Side of Chicago. When he initially arrived, he remembers sharing a room with nine people. Still, it was time to leave his hometown situated between Guadalajara and León for “work reasons.”

“There weren’t many opportunities [in Mexico,]” Vázquez said. “I had to make the decision to look elsewhere.”

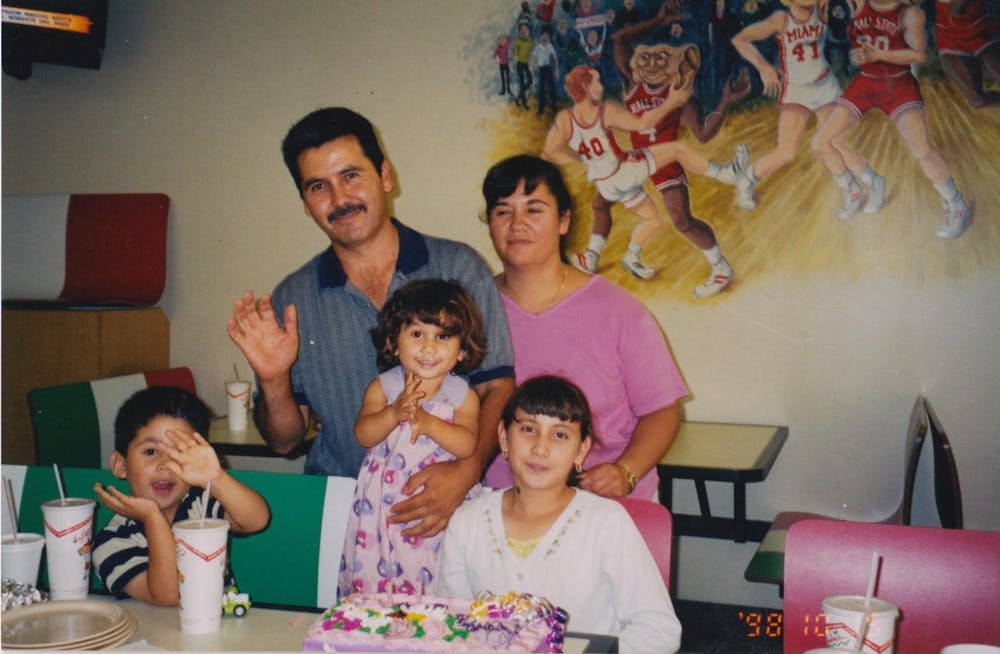

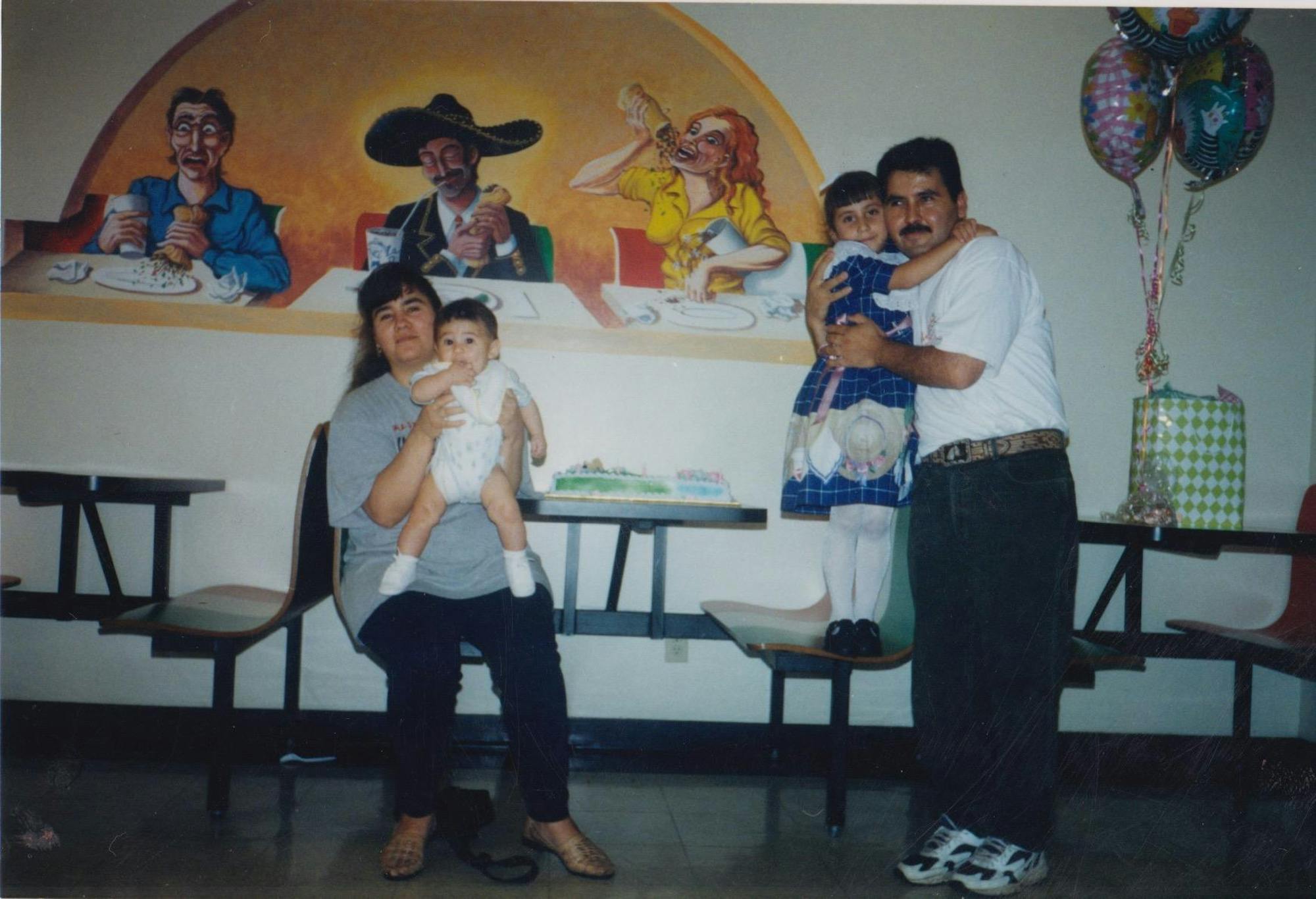

During his time in Chicago, he had a total of three addresses, but by the time he left that Midwestern metropolis in 1995, his living situation looked very different from the room of 10 people he first stayed in. He married and brought over his wife, Ana Vázquez, and they had a 2-year-old daughter, Isabel (now Isabel Vázquez-Rowe.)

His cousin, Ramiro Aguas, is the owner of La Bamba Burritos, a Mexican restaurant that originated in Illinois and is known for having “burritos as big as your head.” The restaurant still has locations in Wisconsin, Illinois, Indiana and Kentucky today.

While in The Windy City, Aguas would often invite Joaquín to work with him in the restaurant chain.

“I thought about it a lot,” Joaquín said of the offer, “until I finally decided, okay, let’s try this.”

As part of joining the restaurant chain, he and his family were put in charge of a La Bamba restaurant at an out-of-state location, causing them to move just a little over 230 miles away.

Their new home would be Muncie, Indiana.

It takes the Village

The Vázquez family only planned to stay two years.

Their La Bamba location was near Ball State University in the Village off of University Avenue.

According to Isabel, the store sat in a mall-like area next to a travel agency, a Buffalo Wild Wings, a hair salon and a flower shop. When the family arrived, the restaurant was nearly bankrupt, and it was up to them to save it.

Upon settling in Muncie, the first things Joaquín and Ana noticed were the accents and the difference in diversity compared to Chicago. They said it took them a while to get adjusted, and even their daughter struggled initially. The pair recalls taking the child to the doctor not long after the relocation.

“We thought [Isabel] was sick, but they told us she had depression as a result of the move,” Joaquín said.

While he would work at the restaurant, Ana would be home watching Isabel and her younger sister Alicia. Similar to her oldest daughter, Ana said it was difficult adjusting, especially when it came to connecting with her culture. She struggled with English, which further complicated things.

In Chicago, the family had many friends and plenty of places to go to find resources such as Mexican products.

“We got to Muncie, and there was nobody [of Latinx or Hispanic descent,]” Ana said. “If I wanted to talk to people, I would go to La Bamba where there were Mexican workers I could chat with.”

In Muncie, if she wanted cooking items like tortillas, she would have to take them from the restaurant. Isabel said the family would often have to drive to Anderson or Indianapolis to find items.

Ana remembers only four Hispanic families living in Muncie in early years.

According to 1990 Census data, there were only 625 people of Hispanic origin living in Muncie at the time. In the same census year, the East Central Indiana city reached its peak population to date, with a total of 71,828 people. This means those of Hispanic origin accounted for less than 1% of the population in the area.

‘We’ve been here’

Nicole Martínez-LeGrand is the curator of the Multicultural Collections in the Library & Archives Division of the Indiana Historical Society. Apart from this, she is Mexican-American and an Indiana native. Her family has over 100 years of history in the northwestern part of the state.

In 2016, she was brought in by the Indiana Historical Society on a grant in order to fill the “biggest gap in terms of representative history,” which was that of Latino and Asian populations within the state. Martínez-LeGrand completed a majority of her work through conducting and recording audio oral history interviews with Latino and Asian Hoosiers. Everything she has collected has come from personal family archives and photo albums.

These materials and research were used to create two separate exhibits focusing on each of the histories. The first of these was entitled “Be Heard: Latino Experiences in Indiana” and was exhibited in 2018. The full collection can still be seen online.

Martínez-LeGrand said not only is Latino history understudied in Indiana, but the issue affects the surrounding region as a whole.

“Whenever you hear about Latino history in the United States, they reference either the East Coast or the West Coast — those large communities who have had [a lot of documented] presence, and I think people seem to think that Latinos did not exist in the Midwest,” she said, “Everybody wants to know when did Latinos get [to the Midwest], and where did they settle and why, but that’s such a personal question to the community because two immigrants, regardless of Latin American heritage, do not have the same immigration story.”

Martínez-LeGrand’s primary interest in her field of study is the Midwestern Mexican diaspora. She mentioned the Mexican Revolution and how it caused many from the country to flee the violence and seek work elsewhere.

She said when she does public speaking events attempting to educate others on the subject, she likes to start with a map from 1847 depicting how a third of the modern-day western United States was Mexico at the time.

“Mexico wasn’t really that far from Indiana, per se,” she said, “and so, with the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in 1848, all of those indigenous and Spanish-speaking people became U.S. citizens overnight.”

According to the aforementioned 2018 exhibit, following World War I and the Great Steel Strike of 1919, many Latinos were recruited to work in affected factories in the United States. One of those was the Inland Steel company in East Chicago, Indiana. Northwest Indiana became a center of Indiana’s Latino community and remains so to this day.

“Historically looking at the census, the two counties with the highest population counts have always been Lake County and Marion County,” Martínez-LeGrand said.

It was not until the 2010 census that Marion County surpassed Lake County in Hispanic or Latino population. The difference between the two counts came out to around 2,000 people at that time.

However, the U.S. Census has a troubled past with counting those of Hispanic or Latino origin. One major issue was citizenship and who was deemed worthy of it, according to Martínez-LeGrand.

“In terms of immigration laws, how we defined who was a citizen was boiled down into white and good moral standing and male which completely disenfranchised women and slaves and indigenous populations,” she said. “I think that has led to our statistical invisibility because the only way you can track populations in terms of a statistical number is the decennial census, and we have been statistically invisible up until 43 years ago.”

She emphasized the importance of the census, saying many don’t understand just how much influence those results can have on a neighborhood.

“Everybody wants a Trader Joe’s or a Target in their neighborhood, and the census depicts that, but it also depicts if you need a hospital, how big is your population,” Martínez-LeGrand said, “so in terms of just general underreporting as a whole, the 2020 census is going to have greater implications throughout this next decade.”

According to the Pew Research Center, it was not until 1980 that the Census Bureau asked everybody in the country about their Hispanic ethnicity. Prior to this, the census numbers were based on national origin, meaning a Hispanic person had to be born outside of the country to be counted as such. As a result, those of Hispanic or Latino ethnicity who were born in the United States were left out, according to Martínez-LeGrand.

Earlier attempts had been made, such as in 1930 when “Mexican” was added to the race categories. To Martínez-LeGrand, this history further underscores the recurring issue of cultural homogenization, or the lack of acknowledgement of diversity, when studying Latino history that she said stems in part from a lack of understanding.

“What I really think about the ‘Latino population,’ the question is how we define it,” she said. “Nobody knows how to talk about our history because Latin America is so diverse. There are so many different countries, and then within those countries, there’s also regional differences.”

Despite the challenges, she said one thing is clear.

“Latinos have been in Indiana and had a significant presence since the late 1910s,” Martínez-LeGrand said, “but Latinos have been appearing on Indiana censuses since the late 1800s, so we’ve been here.”

Creating a community

In the beginning, Ana said the only peace she got was the two or three months the family would spend in Mexico when they visited.

“When we would come back, if one year had passed, it would feel like it had been four,” she said.

This tradition of visiting Mexico yearly remains today, and Ana and her husband help care for family members.

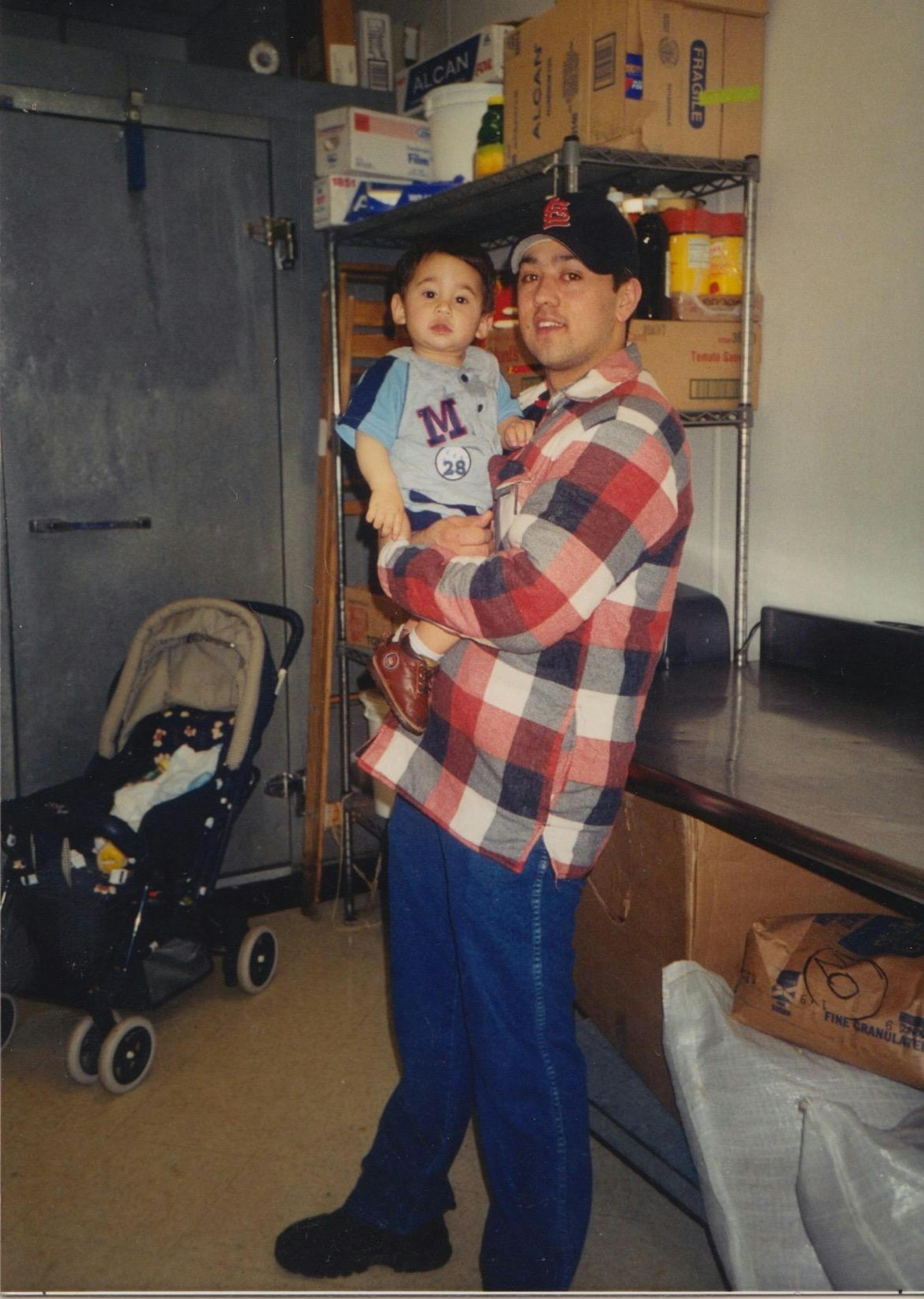

Little by little, however, the family grew into the community of Muncie. The restaurant and its closeness to the university helped form early connections with people in the area, Joaquín said.

“I think La Bamba was a place people went to socialize, but at the same time, the students that studied (at Ball State University) appreciated the help that it gave them in their interest of learning Spanish,” he said.

Ana recalls students coming in and asking to order in Spanish for class assignments. The couple enjoyed having the students around, and it even helped Ana through her own former language barriers at times.

“My husband knew English. I didn’t, but they would still put me at the register to check people out,” she explained. “If I didn’t know how to say something, those same students would help me out.”

They said former students spent time studying there during the days and would describe La Bamba as a “calm” place. By night, that calm environment converted into one of more than 600 customers at times.

“Our busiest hours were typically between midnight and 5 a.m.,” Joaquín laughed.

During these rushes, Isabel would spend time in the back of the shop. Her parents made her a casita, or a little house, out of boxes and baskets with blankets and pillows to sleep in. She still remembers how sometimes shocking it was to witness the crowds.

“When I would wake up, I remember seeing lines full of nothing but students,” she smiled. “It almost scared me. I remember thinking to myself ‘Oh, my God.’”

Despite the occasional chaos, the family worked hard to keep the restaurant clean. When Joaquín initially took over the business, La Bamba owner Aguas would promise to give him $100 every time the restaurant received a perfect score on the health inspections.

“When it turned out that we always received that score, he didn’t want to give it to us anymore,” Ana joked.

As a way to honor the students, Joaquín started to display the perfect score on the wall so the customers could see it.

“I wanted to show the students that I was getting good grades too,” he said.

This small gesture started something much larger when the health inspector saw the score on display within the restaurant. He liked it and decided to begin requiring all restaurants to put their scores where the customers can see.

The family described the great amount of respect and care that existed between the customers and the staff. Joaquín said he looked at those from his staff like they were a part of his family.

“After a certain amount of time, I no longer had to worry about our safety or the restaurant’s safety because the students would protect us and the space,” he said. “Whenever someone was looking for problems with us, they would take care of it.”

To this day, people still recognize the family from La Bamba.

“We made a great deal of friends. It’s something I still miss about our time there. There’s still people that see me and ask me, ‘Are you the lady from La Bamba?’ and I say yes.” Ana said. “It just felt good being there because we all felt like we were doing very good work.”

In 2005, the La Bamba location in the Village moved to McGalliard Road, before leaving Muncie altogether in 2011. The two current Indiana locations can be found in Indianapolis and Lafayette.

‘Ni de aquí, ni de allá’

In today’s time, Joaquín and Ana see ways Muncie has changed for the better in terms of diversity.

“Wherever I go, I see [Latinos.] In the Walmarts, Payless ...” Ana said. “Even now on Independence Day, there are events with mariachis, and there’s church services in Spanish.”

Their daughter Isabel Vázquez-Rowe still remembers the first time she saw another Hispanic family in Muncie. She and her mom were shopping at Walmart.

“It must have been 2008 or 2009, and I looked over and said, ‘Mamá, look!’ and pointed it out.” she said of the experience. “Outside of being in Mexico or in my home or in La Bamba, I had never seen another Hispanic family up until that moment.”

She described seeing other Latinos in Muncie like “seeing unicorns” at that time.

Isabel attended St. Mary School, now known as St. Michael Catholic School after combining with St. Lawrence School in 2021. While she could tell other families did not speak Spanish or share the same culture as her, she said she was too used to it to really notice.

She does not remember being picked on, but she also never brought up her culture when prompted, she said. She described it as a form of “code switching,” a term used to describe how underrepresented groups either consciously or unconsciously alter their language, behavior or appearance to fit into a more dominant culture.

Though she was never ashamed of her background, after attending Ball State and seeing more diversity, she decided it was time for a change.

“I was like, ‘Why am I trying to move and act and think and present as white?’ I’m not,” Isabel said. “I guess I was thinking I just need to honor my family more. At home, I am a mix of Spanglish. Why can’t I be like that outside of the home?”

As a child, she said her father instilled the importance of family in her through their trips to Mexico. Though she had dreams of Disney World trips like other families in her school, her father would tell her, “Tenemos que ir a México; tienes que ver la familia.”

“We have to go to Mexico; you have to see your family.”

Now an adult, Isabel hopes to lead by example for younger Hispanic or Latino people. She mentioned how common she feels negative stereotypes of Mexican people are as part of her inspiration for doing so. Adding more colors to her wardrobe “like her parents would wear” and incorporating Spanish into her everyday life and writing are ways she said she has started honoring her culture more.

“It just became more of a personal thing for me,” she said. “It was more of me saying that this is how I am, this is how I think and this is how I speak. Deal with it.”

She wants younger generations to know there are no set rules to being Latino or Hispanic. The phrase “ni de aquí, ni de allá,” or “not from here, nor from there,” is commonly used in the Spanish-speaking world to describe the challenges children born to immigrant families in the United States face when living between two separate cultures. She said though the phrase is popular, it’s not true.

“You are from here, and you are from there,” Isabel said. “You are in your full right to express yourself in the way that fits you best because you are a mesh of both worlds. In my eyes, that makes you double the person, and that’s fine.”