Chief Munsee never existed.

Despite the legend of a powerful Native American chief roaming the area that would become Muncie being ingrained in the local culture, nothing has been found to confirm the existence of the chief.

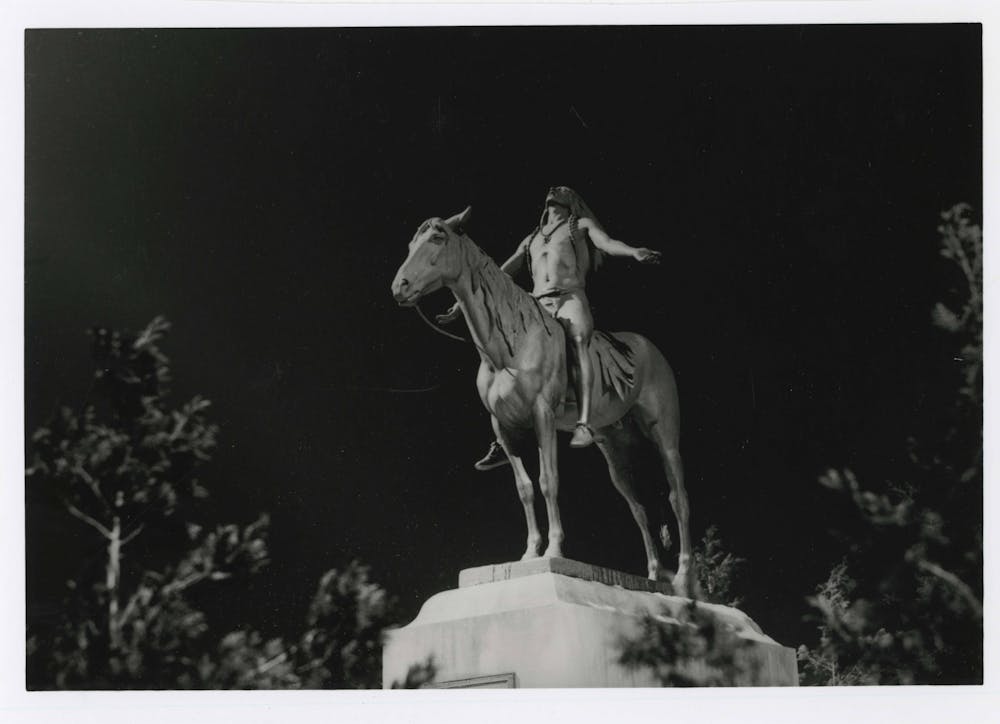

The statue purported to be the fictitious chief located at the split between Walnut Street and Granville Avenue is actually a statue depicting the native people of the Great Plains, who never lived in Indiana. The statue, Cyrus Dallin’s Appeal to the Great Spirit, was placed in Muncie as a memorial to the late Edmund F. Ball, one of the five Ball brothers who helped usher in the modern era of Ball State University.

Chris Flook came across many misconceptions about the origin of Muncie and the name of the town in his life, he said. Flook first got interested in the Native American history of Muncie and East Central Indiana when he started volunteering for the Delaware County Historical Society a decade ago.

“I discovered a lot of my understanding of the indigenous history of the area was fundamentally wrong,” Flook said.

He then got involved with projects to help further research about the indigenous history of Muncie and Delaware County, culminating in a documentary, “Lenape on the Wapahani River,” and a book, “Native Americans of East-Central Indiana.”

Flook’s research focused on the true namesake for both Muncie and Delaware County: the Lenape people who used to inhabit East Central Indiana. More than two centuries after their forced removal, the Lenape’s influence is still being seen in the Muncie community.

The Lenape in Lenapehoking

Lenapehoking is what the Lenape call their homeland, which is composed of most of New Jersey, eastern Pennsylvania and portions of Delaware and Maryland, according to Jeremy Johnson.

Johnson is a member of the Delaware Tribe of Indians, a federally recognized tribe of the Lenape in Bartlesville, Oklahoma. This specific tribe is the largest Lenape tribe in the United States, Johnson, the tribe’s cultural educational director, said.

The Lenape made the territory their own since what Johnson called “time immemorial,” meaning as long as anyone could remember.

“We're considered the grandfather tribe,” Johnson said. “Oftentimes, [other tribes] would come to us to settle disputes amongst other nations because they recognize that we've been there longer than any other nation.”

The Lenape’s first contact with European colonizers came in the 16th century, when Henry Hudson landed on Manhattan Island on behalf of the Dutch Republic. Some time later, Johnson said, the Dutch struck a deal to purchase Manhattan Island, and pushed the Lenape people out of that area.

“They built a wall,” Johnson said. “Hence the name Wall Street … so that was our first forced removal.”

As time passed and the forced removals became more common, some of the Lenape moved north into modern-day Canada with the Mohican people, Johnson said. However, in the 17th century, most of the Lenape were still living in the Lenapehoking.

Johnson added that the name Delaware, which would later become the adopted English name for the Lenape tribe, came from Thomas West, the 3rd Baron De La Warr, who was an English merchant. This name would later be applied to the river that gave the Lenape their English name.

William Penn, the founder of Pennsylvania, had a very good relationship with the Lenape, Johnson said. He mentioned that Penn signed a treaty with the Lenape, promising that no side would take advantage of another.

However, after Penn’s death, his surviving sons “did not feel the same,” according to Johnson, which led to the Walking Purchase, forcing the Lenape west.

“They were refugees from their homeland,” Flook said.

In 1778, the Lenape became the first tribe to sign a treaty with the United States — a two-year-old nation — and France. This made the Lenape the first Native American people to recognize the United States as a separate entity from the United Kingdom, Johnson said. The treaty also recognized the boundaries of the Lenape’s land.

“The bad thing about that was that treaty was never ratified,” Johnson said. “Even though we have held our end of the deal.”

After the American Revolution, the Legion of the United States fought against the Lenape and their allies, leading to their displacement after the Battle of Fallen Timbers in 1794. Thus, the Lenape moved further west into the territory that would become modern day Indiana.

“[The Lenape] were attempting to stabilize their culture, their politics, everything,” Flook said. “They were more or less kicked out of Ohio.”

The Lenape in East Central Indiana

When the Lenape moved to Indiana territory, it was meant to be a land for the Native Americans, Johnson said.

“We were supposed to have two representatives in Congress,” Johnson said. “They never ratified it.”

Flook said the society and the culture of the Lenape adapted to represent their contemporary needs in the early 19th century.

“They lived like anybody else living along this area,” Flook said. “They rode horseback, and they farmed.”

The Lenape also began setting up towns once they settled down in Indiana. These towns would consist of one street; this system of town planning had existed for the Lenape since they lived in Ohio, Johnson said.

“The misconception is we were just still living in Wigwam longhouses,” he said.

Johnson noted that the Lenape who moved into Indiana resisted conversion into Christianity, which impacted some of the tribe’s relatives and closest allies.

“They were forbidden to practice any cultural or traditional beliefs,” Johnson said.

However, despite this resistance, the Lenape still participated in commerce. Johnson called the Lenape “shrewd businessmen” when it came to the economy.

“When the Dutch showed up, we started trading for cloth and ribbon,” Johnson said. “Our women immediately start[ed] making dresses and blouses based on what they saw and liked.”

With each treaty, the United States government, according to Johnson, was supposed to give the Lenape certain necessities. But Johnson said this was hardly the case.

“Oftentimes, we would get the worst of the worst,” Johnson said. “The rancid meats.”

Overall, in their time in Indiana, the Lenape had to participate in what Johnson called “survival-based assimilation.” The land was different from what they were used to in their homelands, and some of their land-based traditions faded away.

“A lot of our designs and themes were very floral,” Johnson said. “A lot of the ceremonies and in those ways were based on what we knew about fish runs and hunting in agriculture … a lot of things were adapted to fit the areas we're forced to.”

Flook noted this assimilation into American culture by the Lenape.

“The differences [are] just that they were Native Americans,” Flook said. “So their culture and their religion reflected Lenape traditions.”

To make up for the loss, the Lenape adapted their traditions to the new region in which they occupied. Johnson said their floral patterns in their traditional clothing changed, and the patterns in their designs became more “geometric” than before.

“We start to see diamonds and more rectangular [patterns],” Johnson said.

He also noted the importance the members of the Lenape who resisted Christianity had in keeping these traditions alive until the present day.

When the Lenape lived in East Central Indiana, they were allied with various tribes. Flook noted that the Miami were closely allied with the Lenape; Johnson said their closest allies were the Shawnee who Johnson considers their “relatives.”

The name “Muncie” has roots in the name of one of the two main languages the Lenape spoke — the Munsee language. Flook said the primary village the Munsee speakers lived in was called Munseetown, located where Minnetrista is now.

Flook noted at the time Muncie was incorporated as a town, there was no agreed spelling of the town’s name. Over time, the spelling of Munseetown became Muncietown, then the Indiana state legislature shortened it to just Muncie in 1845, Flook said.

“Then the post office, which is a federal government office, did the same thing,” he said.

By the time the name change happened, the Lenape were gone from Indiana. The Treaty of St. Mary’s, ratified in 1818, led to the purchase of Lenape land in Indiana and their eviction. The Lenape then spread out; Johnson said some Lenape went up north to settle in Wisconsin, while others continued onto Kansas, then Oklahoma, where the Delaware Tribe of Indians are today.

Reconciliation and the Future

In Northern Indiana, the Miami Tribe of Oklahoma, one of the Lenape’s allies when they were in Indiana, owns ten acres of land in Fort Wayne which the tribe uses for cultural preservation.

Diane Hunter, the Tribal Historic Preservation Officer for the Miami Tribe of Oklahoma, said the Miami had been in Indiana since “time immemorial,” the same phrase that Johnson used to describe the Lenape and their homeland.

“Indiana is the land of the Miami,” Hunter said.

Shesaid she believes people are not being properly educated on Native Americans; therefore, misconceptions and stereotypes are being formed.

“It's still not happening in the schools like it should be happening,” Hunter said. “[The Miami] try to educate people as much as we can … but there are very few people who can do that.”

Hunter hopes , in the future, Native American history will be taught in a more appropriate manner than in the past.

“Let's take out the focus on the American bias,” Hunter said. “It's still focused, as this is what the Americans did.”

Jackson said the Lenape are welcoming and accepting towards reconciliation. He said the first step towards reconciliation is by keeping an open line of communication with the tribes.

“I think it's important that folks actually reach out and speak to the people that are wanting to either educate about or dealing with [Native American history],” Johnson said.

There are many places named Muncie or Delaware across the United States, Jackson said. However, Jackson said it is “helpful” for these places to bear the name of the Lenape.

“It's a reminder to our folks, this is where we came from,” Johnson said. “This is an area that we inhabited at one point.”

Johnson hopes to be able to collaborate on more projects in the future to help educate people about the Lenape tribe. He said it is a goal of the Lenape to reestablish relationships with former lands they have occupied. The Lenape have begun this process in Pennsylvania and New Jersey with various programs, universities and government entities.

To that end, he hopes Muncie’s government will be able to welcome the Lenape into the community and reestablish connections, he said.

“We're trying to be ambassadors for our culture and history,” Johnson said.

Hunter also noted the importance of talking to members of tribes, specifically the tribal government, when concerning Native American imagery. She has had conversations with various towns about Native American imagery and names and noted that working with the tribal government is beneficial for understanding.

“Talk to people like … the elected leadership of a tribe to get their cooperation and permission before choosing those names,” Hunter said.

Flook noted the research being done about the Lenape in Indiana has led to information about the tribe becoming more accessible.

“It's easy to find this information,” Flook said. “I find the topic absolutely fascinating.”

For Flook, the best way people can combat the misconceptions of the Lenape and Native American people is by being willing to learn.

“They have real 21st century needs,” Flook said. “They're not some fossilized relic of the past. They have this rich, dynamic history, and they deserve assistance.”

Contact Grayson Joslin with comments at grayson.joslin@bsu.edu or on Twitter @GraysonMJoslin.