Shaky, handheld cinematography has become increasingly popular in cinema. Audiences tend to like real, seemingly truthful situations in their media, and what better way to achieve this by using a shooting style anyone can achieve with a smartphone? This style of filmmaking places audiences directly into the action of events and seems all the more real and relatable. Typically we see this style in the horror genre (think Blair Witch or Cloverfield), but what about other genres? More specifically, what about documentaries?

While documentaries are not typically based around fictional characters and elaborately crafted narratives, this style can be seen in documentary film. We call this technique Cinema verite.

Cinéma vérité (literally: “true cinema” in French) is a film movement from the 1960s that aims to capture real people and situations in as truthful a light as possible. This is done with minimal editing, authentic dialogue, and minimalistic camerawork (typically handheld).

Image from cineCollage

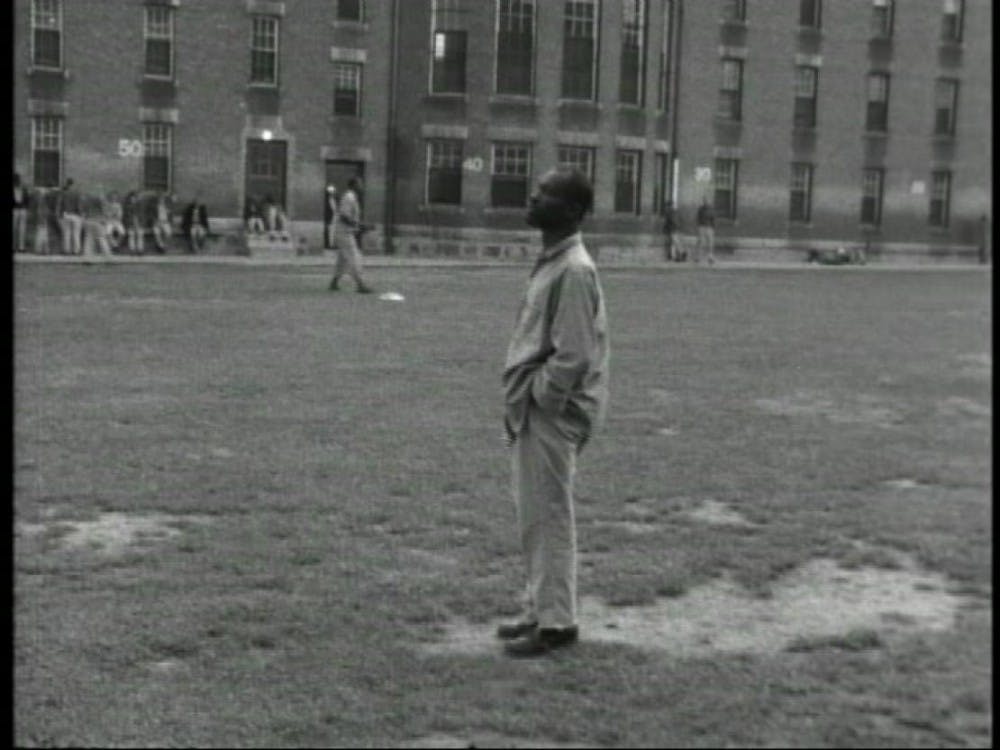

Frederick Wiseman’s controversial documentary, Titicut Follies, is a prime example of cinema verite. The film is largely known for revealing the deplorable conditions of Bridgewater State Hospital, a correctional facility for the criminally insane in Bridgewater, Massachusetts. In the documentary we are shown images of inmate neglect, dehumanization, and verbal abuse. The film is shot quite simply with minimal editing and basic camera shots. The way the film is framed makes you feel like you, yourself, are in the facility with the inmates witnessing the abuse. Because of this direct, blunt style of filmmaking, the film is difficult to watch and is an emotionally taxing experience.

Image from WickedHorror

But what about the impact of the inmates being shown on film? We know the impact Wiseman wanted to have on the viewers, but in his quest to make a statement did he invalidate the rights of his subjects? Many of these people were not capable of providing consent given their mental state. Were their rights violated? Were they not given proper respect or consideration?

The government of Massachusetts certainly believed this to be the case. In 1967, just before the film was set to be shown at the New York Film Festival, the state of Massachusetts stepped in claiming that the film violated the inmate’s rights to privacy and portrayed them in an undignified manner. The film did ultimately premiere in New York despite these concerns but was banned from distribution the following year and was not publicly distributed until 1991.

There are certainly aspects of the film that could be considered a violation of the inmates privacy, namely the emphasis on specific inmates. Many shots focus on subjects for extended periods of time, drawing out uncomfortable scenes for long stretches and giving specific subjects primary focus. Witnessing mentally ill inmates stomping around naked and screaming in an unfiltered, uncomfortable manner is a consequence of cinema verite which aims to show reality in its raw form. While these close-ups and extended shots could aid in a case against the film for lack of human dignity, this would be a moot point if permission was granted for filming subjects.

Image from CriticalCommons

The problem is that Wiseman did receive permission to film from Massachusetts Lt. Gov. Elliot Richardson and Atty. Gen. Edward Brooke. Wiseman addresses this briefly in and interview with Filmmaker Magazine:

“To get permission to film inside Bridgewater Hospital, Wiseman said he ‘told them from the beginning the kind of movie I was doing.’ He said he made it clear that the film would be shown widely and that he’d get final cut. ‘I always make a full disclosure of the method and the procedure,’ he explained. ‘It’s extremely important to make a full disclosure about what you’re doing – not only is it the ethical thing but it also means nobody can come back at you if they didn’t like the movie.’”

Interestingly, Richardson would later become vocally outspoken about removing the film from the New York Film Festival. Considering that Richardson initially okay-ed the project, it seems strange that these concerns were not addressed prior to filming.

Image from WBUR

Well what about the issue of consent? Not all of the inmates were capable of providing consent themselves, but Wiseman insists that in these instances he did receive the consent from their legal guardian, the hospital superintendent.

The next logical issue that comes to mind is a concern for the family of the inmates. How would they react to seeing their loved ones portrayed on screen in such terrible conditions? This is addressed in the 1991 LA Times article, Titicut Follies’ Arrives, 24 Years After the Fact, where Massachusetts Supreme Court Judge Andrew Gill Meyer, the judge who eventually overturned the film’s ban affirms that since 1967, “… no Bridgewater inmate or inmate’s relatives have pressed a claim against public showings of ‘Follies”. In the 2016 interview with Filmmaker Magazine, Wiseman confirms that 25 years after the film’s public release no former inmate or their family has publicly spoken out against the film. While the lack of public outcry by no means proves no offense was taken by ex-inmates or their relatives, there is no legal case made by those involved regarding degradation or invasion of privacy.

So why then, was the film really banned? My theory is that there is far more of a political impact than a moral one. While the issue of human rights vs. freedom of expression certainly comes into play, it is highly unlikely that those in government positions were as concerned about the inmates rights as they would like one to believe.

Let’s look at the context in which the film was made. The 1960s was a transitional period for mental health treatment in the United States. According to Young Minds Advocacy, during the 1950s, “Rates of institutionalization had exploded over the prior half-century: by the mid-1950s, over half a million children and adults were institutionalized for mental illness. This number represented a thirteen-fold increase overall and a growth rate nearly five times that of the general population since the late 1800s.” During this time, many began to question the effectiveness of institutionalization. Many patients would enter these institutions, receive little to no treatment, and would not be released for extended periods of time.

The implementation of the Community Mental Health Act of 1963, a federal policy that shifted focus from large metal health institutions to community focused ones, was a proposed solution to the issue. Sadly, the policy had the opposite effect.

Image from The National Council

Reports at the time indicated significant abuse of patients and a general lack of credible mental health care. The idea was that funds would be redirected from the states to local communities to manage and monitor the needs of individuals with mental health issues. Unfortunately, this transfer of funds never happened and local communities were simply overwhelmed.

With this in mind, we can see that Titicut Follies was conceived at a time of major corruption regarding mental health. Prior to filming in 1966, Wiseman had visited the Bridgewater State Hospital multiple times as an instructor. He had taken students on field trips to the institution and had likely witnessed the poor conditions on multiple occasions before deciding to film Titicut Follies. Because of the legal developments surrounding mental health at the time and Wiseman’s various trips inside Bridgewater, it is obvious from this context why he would want to make the documentary that he did.

So here we have a policy that on the surface aimed to rectify mental health institutions, but resulted in overcrowding and mismanagement. Then a filmmaker comes in and films the corruption inside of a mental health institution only to have his film banned by the local government citing “privacy concerns.” But were the concerns really for the inmates? While we can’t say for certain the answer is no, the situation reads far more like a government cover-up than an attempt to protect inmates. It seems like the concern was for those whose political careers would be negatively affected once the current state of Bridgewater State Hospital, and on a larger scale all American mental health hospitals, was revealed to the public. Wiseman supplements this ideas in the Filmmaker Magazine interview by simply stating, “It was banned for political reasons”.

The reveal would expose the inadequacies of the Community Mental Health Act of 1963 and force more attention to reform. And this did eventually happen after the film’s first release. All state-run mental health institutions closed in the 1970s. While this was not solely a result of Titicut Follies, the film definitely played a massive role in exposing the terrible conditions of these hospitals.

There is a lot to digest here. Morality, filmmaking ethics, political motivation, and censorship are all valid topics when discussing Titicut Follies. All of these ideas can be explored from various perspectives, but in the end, it feels disingenuous to accuse Wiseman of lacking empathy for the inmates and using their image without regard for their well-being.

Image from The Anthropology Diaries

Cinema verite focuses on capturing reality as is. This means if what is being filmed is uncomfortable, what we see on camera will reflect that truth. Should the film be censored to protect subjects in the film? No. Considering no one has come forward with complaints (outside of government officials who would benefit from the film being banned) and Wiseman took the appropriate measures to gain permission to film, the issue of privacy seems to be a moot point. In regards to the style it was shot in aiding the unfair portrayal of the inmates, the film was made purposefully in this realistic approach, not to disregard inmates’ well-being or to make a joke out of them, but for the purpose of informing the public of their living conditions and treatment. Subjects are given extended screen time to highlight their living conditions, discuss their mental state, and show just how long and drawn-out the suffering was. There is no ill-will or malicious intent here: just a focus on the truth.

When it comes to morality, we need to be careful to consider the context of a work and the intent in releasing it. On the surface, the controversy surrounding this film stems from a lack of human regard and well-being. Yes, we should always consider the subjects well-being, and that is precisely why the film was made, to showcase that the institution was not working to protect those in its care. In this process, did Titicut Follies end up harming the inmates? No. The only one harmed by the film were the corrupt institutions that housed them and the politicians that failed to enforce true reform. The question we then need to ask are the ones who were “saved” from the film’s ban the inmates or the politicians? Based on the evidence provided, I am inclined to say it’s the latter.

Sources: Encyclopedia Britannica, Filmmaker Magazine, LA Times, Young Minds Advocacy, The National Council

Images: cineCollage, WickedHorror, CriticalCommons, WBUR, The National Council, The Anthropology Diaries

For more entertainment, tech, and pop culture related content, visit us at Byte BSU!