Following a nationwide trend, a gender gap still exists between male and female faculty in the sciences at Ball State.

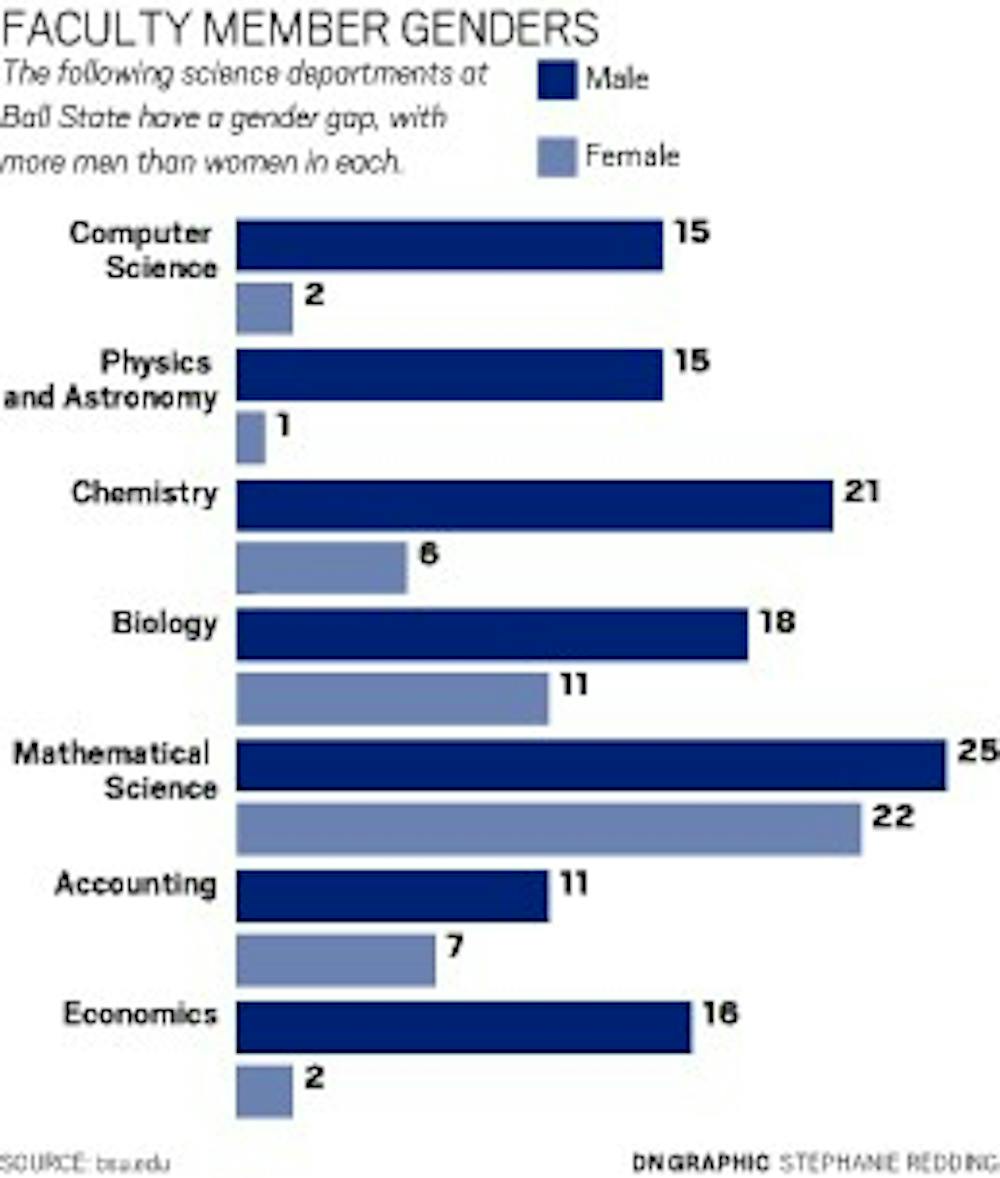

At Ball State, there are 65 male and 19 female professors and instructors in the computer science, physics and astronomy, chemistry and biology departments combined.

Nationally in 2011 women made up 41 percent of life and physical scientists and 27 percent of computer professionals, according to a Census Bureau report. Data from the National Science Foundations shows only 21 percent of science professors in America are women.

Thomas Jordan, chairperson of the physics and astronomy department, said the difference in the numbers is not due to an intentional bias, but because of alack of women in the hiring pool. Jordan said there were around 30 applicants last time the department was hiring, none of which were women.

“It is not intentional,” Jordan said. “We are certainly looking for women here to be role models for our women that major in physics. They need a role model. I certainly can’t be a role model. I can encourage, but it’s more like a father. It’s a whole different point of view.”

The gender gap is apparent with students as well. There are eight female as opposed to 64 male physics and astronomy majors, 73 female and 97 male chemistry majors and 33 female and 271 male computer science majors at Ball State. Although there are more male than female professors in the biology department, that disparity is actually reversed by the number of undergraduate students: 566 are female compared to 374 males.

Paul Buis, computer science department chairperson and an associate professor, said that although he is concerned about undergraduate numbers in the computer science program, he isn’t as concerned about graduate students, due to the amount of international students that participate in the program.

“The gender balance issue is local to the United States,” Buis said. “It is not a worldwide phenomenon. Of our international graduate students, we’ve got plenty of female graduate students. I’m not sure why the imbalance exists only in the United States, [but] it appears to be a cultural thing as opposed to some kind of genetic predisposition of people’s skills.”

Melinda Messineo, the chairperson of the department of sociology and associate professor of sociology, said accepted gender roles are one main cause of this imbalance within the U.S.

She said when young men or women are learning how to fit into society they are taught to perceive appropriate gender roles. This can have a large effect on the path a person sets for themself.

“Mentoring in upper grade levels and in college can also impact the paths that people choose,“ Messineo said.

Not only are women seemingly shying away from certain science careers, but Buis also thinks some males who should consider different careers sometimes get degrees in sciences. Socialization can just as easily lead to men majoring in science, even if it is not their specialization.

Buis said although there may be more men, about half, if not more, of the top 10 students in a science class will be women.

“Women got into it because they’re good at it and enjoy it,” Buis said. “That’s the right reason to get into things. The better question is why do guys go into disciplines that they aren’t good at?”

Heather Bruns, an associate professor of biology, said she thinks the somewhat traditional view that men are more likely to pursue a career in the sciences is fading.

“I think that perception that ‘women can’t do it’ is less,” Bruns said.

Although Bruns never felt being a woman made getting her degree more difficult, she said it impacted what she decided to do with that degree, which she thinks could explain why there aren’t as many women leading labs or classrooms. Bruns opted for a career with less research so she could be the primary caregiver. It also impacted her decision to not to do postdoctoral work.

This trend is national with data from the magazine American Scientists showing that women who hope to have children are twice as likely to stop trying for an academic research position.

Bruns also said one of the three women she graduated with stopped working to raise a family, another option which leads to fewer women with teaching positions.

Bruns said despite being in the minority, she has never noticed discrimination.

“I have to say, I’ve had a really blessed, charmed experience,” Bruns said. “I feel like I’ve been very supported and not because of whether I’m a male or female.”

Lan Lin, a computer science assistant professor, said being a female can even work to a person’s advantage.

“In certain ways, you get more encouragement because you are female,” Lin said. “For instance, if you are doing job hunting and you are a female under the same conditions, people want to hire you because a large part of the workforce is male dominated.”