Sophie Nulph is a senior magazine journalism major and writes “Open-Minded” for The Daily News. Her views do not necessarily reflect those of the newspaper.

When asked as a little girl what I wanted to be when I grew up, I never said “teacher” or “ballerina” or even “journalist.” I always said, “a mom.”

My childhood best friends were my three American Girl Dolls named Juli, Claireice and Kit, along with my two Bitty Baby twins, Carter and Chloe. I was their mom, and we spent every waking moment together. I had a particular bond with Juli, a Christmas gift from my grandparents, whose imaginary presence to me was comforting for a girl who never really fit in.

I finally retired my American Girl dolls when I was in sixth grade, when we moved out of my childhood home and I was determined to “grow up,” but my need to nurture never went away. After my dolls, I turned to babysitting and pet-sitting. I put all my love and care into my niece and nephew, who suddenly lived within 500 miles of my parents’ house for the first time. When I got to high school, I applied for a job at a daycare, starting with 3-year-olds and working my way down to infants. Those 3-and-a-half years were consumed by wonderful memories of firsts and warm baby smiles, and they only made me want to become a mother more.

My inherent need to nurture comes from my mother, the strongest woman I’ve ever met. While emanating the definition of feminism in a man’s world, she is called “mom” by a community of people. Women have always represented a nurturing lifestyle, simply because evolution allowed women to carry and give birth, rather than men. Women traditionally cooked, cleaned, bore the children, educated them enough to work and supported the men in every way possible. Women have always been built with the superpowers to nurture, support and maintain independence — wondering when exactly they will reach the breaking point in womanhood.

While not every woman wants kids, most women have the capability to have them, as evolution shows. So, what happens to a woman when she doesn’t? Is she no longer considered a “whole” woman? What happens when the only thing you want when you grow up is to have little kids of your own to impact and teach and help grow, only to discover there’s a chance you may never be able to have kids at all? Women aren’t taught “what’s next” when they choose not to have kids or are unable — they are simply asked “why?”

The Center for Disease Control and Prevention confirms an estimated 10 percent of women in the United States, more than 6 million, have fertility issues when they try to conceive. In accordance, between six and 12 percent of women have been diagnosed with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), a hormonal condition where the ovaries create an abnormal about of androgens — the male sex hormone — that present themselves most commonly after the formation of cysts, or fluid-filled sacs that grow on the ovaries. While this does not mean all women with PCOS have cysts, everyone diagnosed runs the risk of fertility issues and endometriosis, a disorder that grows uterine lining outside of the ovaries.

With an increased amount of androgens in the ovaries, it is harder for the organ to ovulate a mature egg ready for fertilization. As a result, PCOS is one of the most common causes of infertility among women.

In fact, a 2015 article published by “The Journal of Endocrinology and Metabolism” explored the relationship between PCOS diagnosis and infertility procedures. The study found there was a 26.4 percent correlation with PCOS diagnosis. Yet more than 50 percent of women go undiagnosed due to out-dated criteria and lack of education that quiets the condition.

That’s a problem for a disease that affects one in every 10 women.

If women’s bodies were supposedly made to conceive, what do we do when they fail us in doing so? Education fails to raise awareness to the realities of genetics, leaving women who struggle with these issues feeling hopeless and alone.

I was diagnosed with PCOS in 2020 as an indirect result of a YouTube video. At the time, I was trying to lose weight, and I was following a lifestyle influencer, Remi Cruz, on her weight loss journey. She posted a video one day titled “I have PCOS,” and I clicked on it. I left convinced I had the same problem and self-diagnosed myself. Six months later, my sister was diagnosed with PCOS by an actual doctor, and that’s when I found out my mother and grandmother had it as well. I went to the same doctor a few months later, and after far too much blood work, the reality of my situation suddenly became all too real to handle.

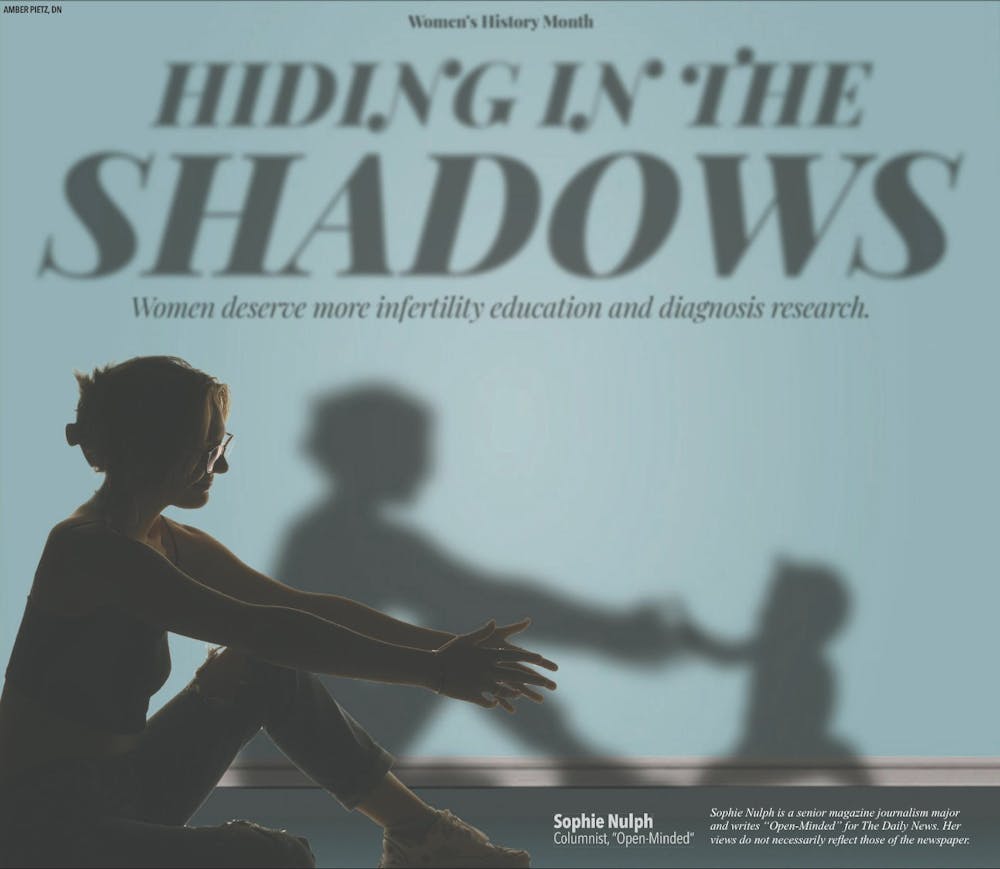

I felt my womanhood crumble around me sitting on that examination table. I never questioned my identity as a woman, but my diagnosis cast a thick fog over what I felt was my purpose as a woman entirely. All I could think about was the possibility of being infertile, and it crushed me and my dreams of motherhood.

I didn’t know what the condition was, even with my mom’s diagnosis, so I never understood what it meant to only have a period twice a year. I never understood why I couldn’t lose weight like the other girls due to the metabolic issues PCOS causes in some women. Now, I wake up everyday knowing there’s a possibility I won’t be able to have kids, and that thought itself makes 6-year-old Sophie cry into her worn out Minnie Mouse stuffed animal.

While it’s possible for me to have children in other ways, the pain of knowing I may never experience pregnancy — the magical gift of growing my own baby — forces waves of numbness through my body until my eyes burn and my throat narrows. All I’ve ever wanted is to be a mom, and while I have never experienced the loss of a baby or can comprehend the pain that brings, I understand the longing of a child that may never be.

If I would have known this was a possibility when I was younger, I might have been able to prepare myself for the uphill battle of advocating for myself. The condition’s impact, able to show itself at birth and form later on in life, shadows over the education in sex eduaction and intial OBGYN visits.

There is still hope that I can have kids, if I continue to treat my PCOS and be careful with my diet and exercise to prevent diabetes. I found that hope in the shadowed community of PCOS support groups filled with women supported women struggling with an uncommonly known condition. Further education for young minds can further inform ways to treat PCOS and more research for diagnosis can lead to more specific medications to help. My PCOS story is not necessarily one I anticipated sharing, but I hope, through my vulnerability, to educate others on an issue no woman should face alone.

Contact Sophie Nulph with comments at smnulph@bsu.edu or on Twitter @nulphsophie.