John Lynch is a senior journalism news major and writes “Fine Print” for The Daily News. His views do not necessarily reflect those of the newspaper.

Everyone above a certain age can remember where they were on 9/11.

That’s not hyperbole — I’ve never met someone above the age of 30 who can’t remember where they were, what they were doing or how they reacted to the events of Sept. 11, 2001.

The same cannot be said for people my age, members of what we would call Gen Z.

In September of 2000, my parents visited a family member who was living in New York City at the time. During their trip, they toured the World Trade Center and brought me with them. As I was just 5 months old at the time, I can’t remember anything about the visit, but the fact I was there just a year before the tragedy has been treated with a certain level of reverence among people older than me.

That was difficult for me to understand.

Unlike our millennial predecessors, very few people my age can remember what 9/11 was like, much less describe the way it made us feel. We were, however, left to grapple with its effects from the moment we were able to form memories.

Many people my age learned what the war on terror was in simplistic, morally black-and-white terms, only to be stuck with the war on terror and its effects for the entirety of our childhood and transition to early adulthood. As we grew and changed, so too did the war.

America’s mission in the Middle East began relatively simply: Bring the perpetrators of 9/11 to justice. That mission dragged on for years until Osama bin Laden, the leader of al-Qaida and the leader behind the attacks, was killed in 2011.

That, I do remember. I was in fifth grade May 2, 2011, when it was announced that a team of Navy SEALs had found and killed bin Laden in Pakistan. I remember watching the news with my parents and seeing then-President Barack Obama tell the nation that the hunt for al-Qaida’s leader had ended.

I remember thinking at the time: “Great, the war is over! We won!” How wrong I was.

During my middle and high school years, the prominence of the United States’ mission began to diminish. Sure, there were signs of progress in the region like the expansion of human rights for women and girls and the beginnings of a U.S.-sponsored democratic government, but the shadow of the U.S.’s hand was ever-present. I became more politically conscious and began to resent the war’s length.

Now, the mission is over, and there is painfully little to show for it. As of Aug. 15, 2021, the Taliban are back in control of Afghanistan. Any “progress” that was made in the region is being undone, and there’s very little we can do about it. While President Joe Biden has committed to helping people leave the country via diplomatic missions, our efforts in the region are effectively finished.

For as long as I can remember, our country has been playing nation-builder in Afghanistan, but our motivations were never fully within my grasp. I think that experience is common among plenty of people who never saw the towers fall.

Even with its presence throughout the entirety of our child and adult lives, what stake could my generation possibly hope to have in a battle they never asked for?

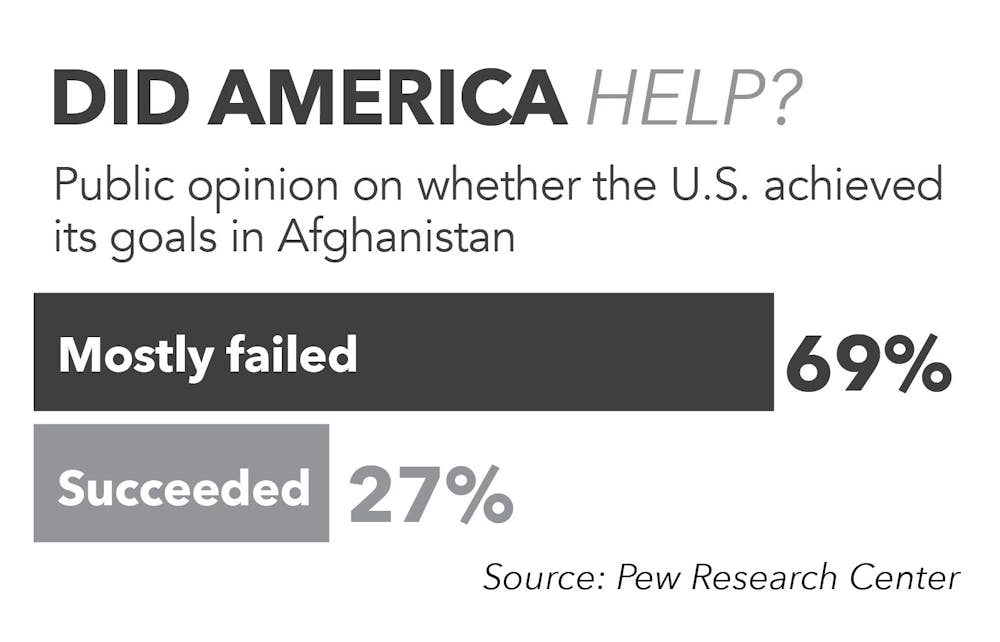

America and its allies’ efforts in the Middle East have been a stain on our international image and a drain on our resources. More importantly, it’s been a cultural wedge that has only worsened our divided political mind — according to research by the Pew Research Center, 54 percent of Americans say the U.S. was right to withdraw from Afghanistan, while 42 percent supported staying.

Let that sink in: even after 20 years and clear evidence that our interventions have had very limited lasting positive effects in the region, a significant portion of Americans still want to try the same thing, expecting a different outcome.

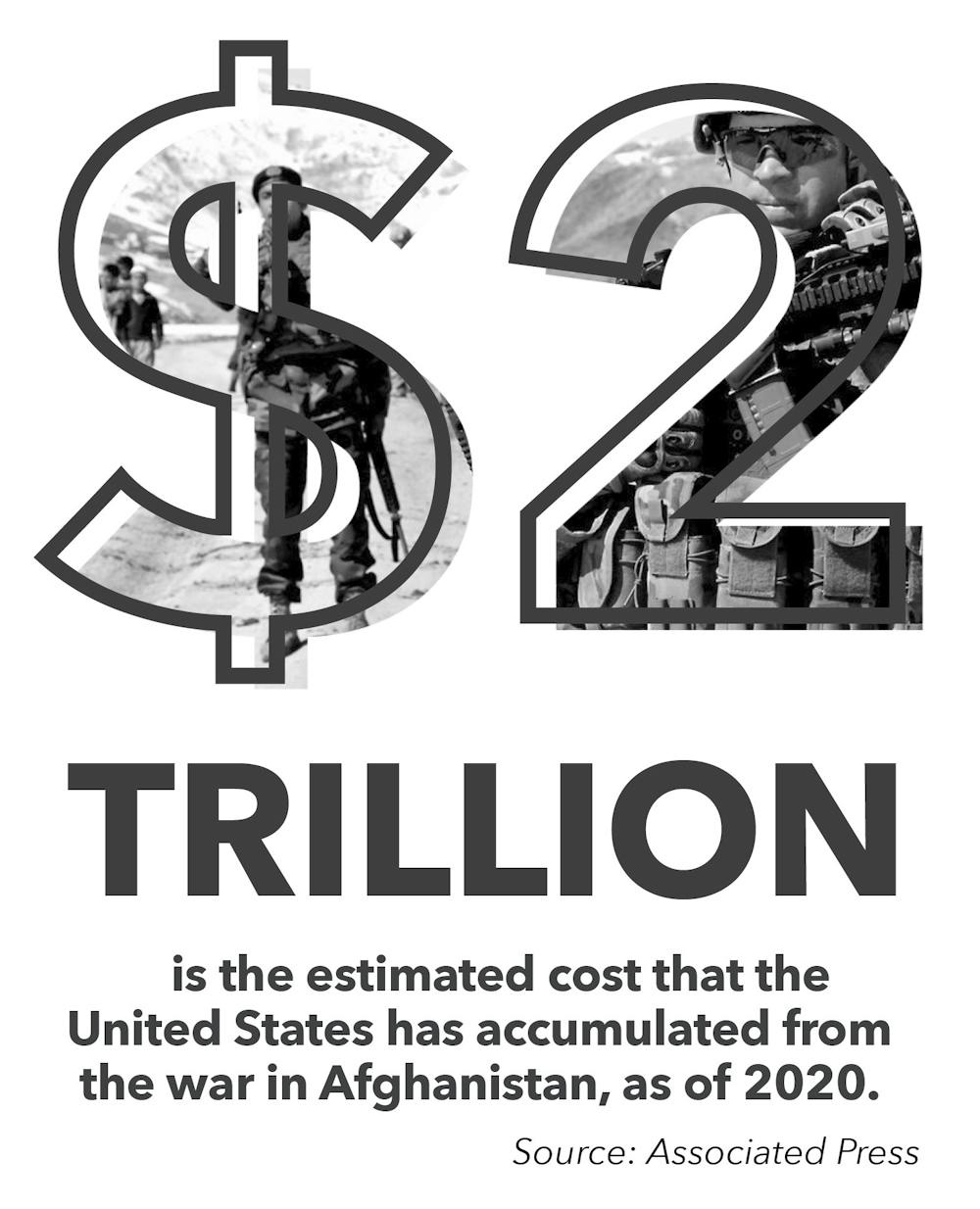

That’s shocking, considering the widespread failures it has caused at home and abroad. Estimates by The Associated Press (AP) of the current cost of the war place the U.S.’s spending on war-related costs in Afghanistan and Iraq since 2001 at around $2 trillion — good for a cool $300 million for every day the United States stayed in the country.

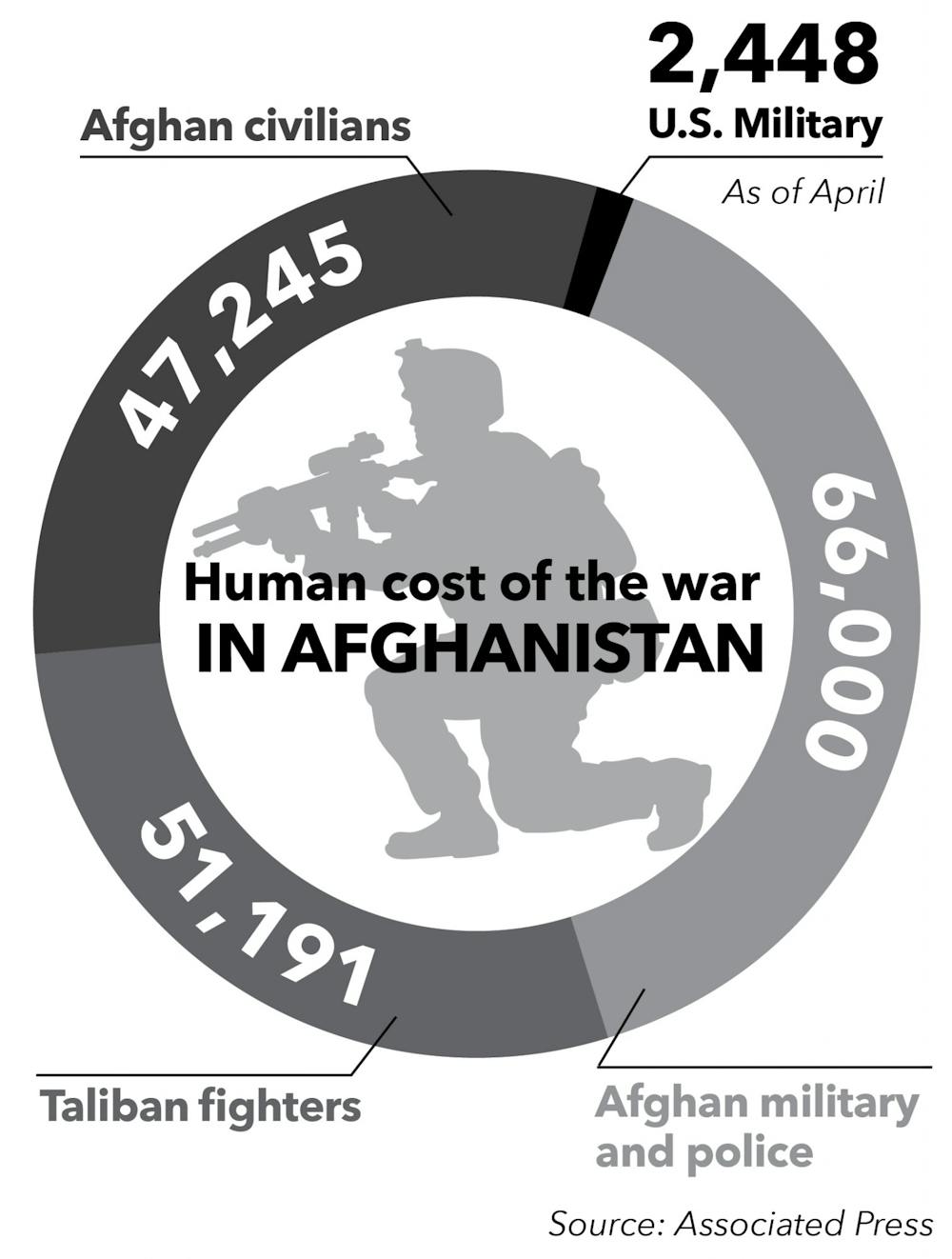

More importantly, the human cost of the war has been grotesque. The AP estimates 2,448 U.S. service members lost their lives in the conflict, while the Taliban lost 51,191 total fighters. Worse still, the Afghan population suffered heavily as a result of the fighting, as 47,245 civilians were killed over 20 years.

Look, there is a lot to criticize about the way the withdrawal from Afghanistan has gone so far, from former President Donald Trump’s deal with the Taliban to the Biden administration’s inability to prevent the Taliban’s takeover of the country during the withdrawal, but, at the end of the day, removing our presence in Afghanistan was the right thing to do.

Twenty years of futile warfare have proven this point. My generation, perhaps more than any other, is tired of this war and its effects. The best we can do now is to provide aid to those in the region who want it and to move on as a nation.

The failures of the United States in Afghanistan have revealed to many people my age the flaws in our country’s priorities and the system that has chosen imperialist goals over our domestic welfare. My generation has never known the fire that motivated our predecessors to embark on this foreign policy disaster in the first place, and, now that it’s over, all we’re left with is the smoke of our national shame.

Contact John Lynch with comments at jplynch@bsu.edu or on Twitter @WritesLynch.