Every morning, she wakes up at around 5:30 a.m. to go outside.

“It’s before you can see anything because that's when the birds are starting to sing,” the associate professor of educational studies said.

For Annette Rose, bird migration in the spring is more of a holiday than a seasonal occurrence. Being the president of the Robert Cooper Audubon Society makes bird watching and other conservation-related activities a big deal to her.

“They give me pure joy,” she said.

Living in Indiana means Rose like other Hoosiers get to see different birds passing through the state during migration.

While winters are quiet, the spring season brings with it the familiar bird calls as the weather warms up.

As the weather warms up, birds migrate northward in what’s known as spring bird migration.

The Cornell University Lab of Ornithology’s (CLO) website All About Birds defines spring bird migration as when birds “tend to migrate northward in the spring to take advantage of burgeoning insect populations, budding plants and an abundance of nesting locations.”

Kamal Islam, professor of biology, listens to the sounds of birds on his way to work. Ornithology, being his main research interest, means he’s familiar with bird calls.

“I heard my first Baltimore oriole just this morning,” Islam said.

Birds like the Baltimore oriole, use Muncie as a stopping point before continuing their migration up north, Islam said. This time can be very exciting for the birdwatching community he said Islam, like Rose, looks forward to the seasonal migration like it’s a holiday.

“It’s just a lot of fun,” he said. “I call myself a birder and we birders are very passionate.”

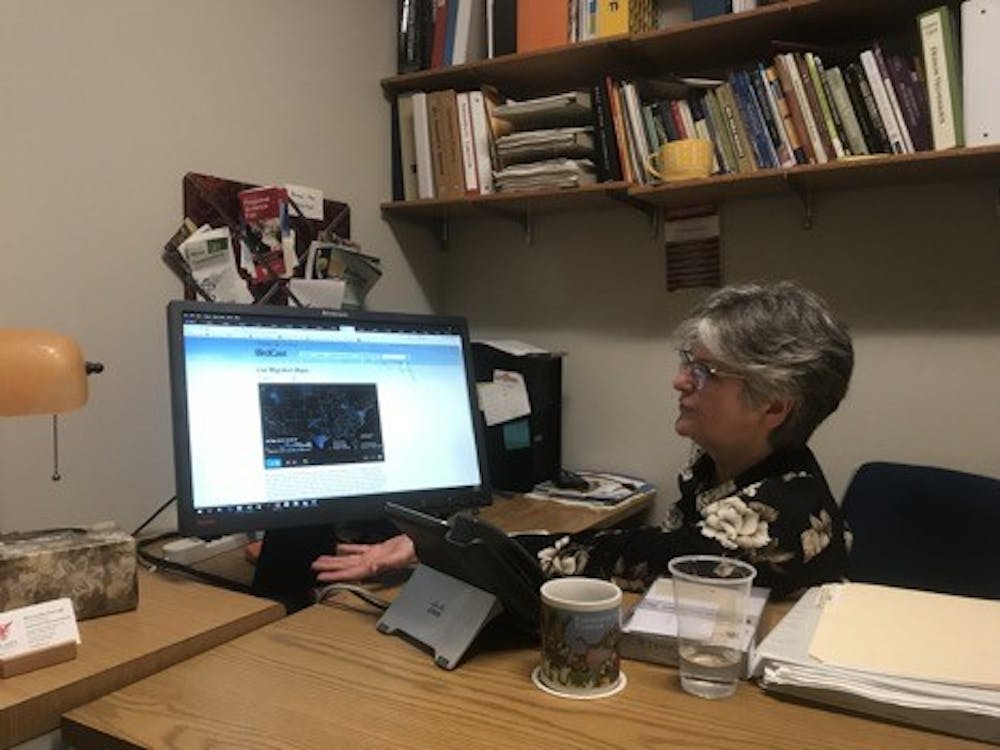

Annette Rose, associate professor of educational studies, discusses the importance of bird migration while going over an interactive map showing migration intensity. Some birders watch these maps and make decisions about where and when to go for birdwatching. Chase Martin, DN

CLO’s website Bird Cast shows live migration maps of real-time bird migration patterns as detected by the U.S. weather surveillance radar network.

“Very intense birders will watch these maps and deliberately make decisions about where and when to go because of the concentration of species at that time,” Rose said.

The first weeks of May serve as the peak time for locals to see birds passing through. Places like Summit Lake State Park as well as Ball State’s Christy Woods welcome hundreds of different species each year, Islam said.

“[Summit], has a variety of different habitats,” he said. “It has open bodies of water, which attract waterfowl and small woodlands that bring songbirds to the area.”

For some birds, the Midwest serves as a checkpoint for the migration. Places like Muncie can see different species throughout the season, Rose said.

Islam said May is an “exciting time” for bird watchers.

Certain species of birds travel several hundred miles from places like Central and South America. Birds have a built-in compass that helps them get to their destination, he said.

“It’s not innate, it’s learned,” Islam said. “It allows them to cross large bodies of water and not get lost.”

At night, birds travel “thousands of feet in the air” and rest during the day, Rose said.

According to the National Weather Service, Muncie has seen a slight change in the climate where warm weather is coming later than usual.

This change has had an effect on bird migration patterns. Islam said a change in temperature is one of the signs for birds to begin migrating and with spring arriving late, birds migrate 10 to 12 days later than usual.

“When you change those kind of patterns that have taken hundreds, or maybe thousands of years to develop, then you’re going to see some immediate effects,” Rose said.

Without birds serving as a natural predator for insects, the population of the insects will rise up, she said.

“This planet is occupied by a genetic pool that is so broad,” Rose said. “If we can maintain that diverse gene pool it gives me hope that others will find peace in what exists and not to try to exploit every natural resource that we have.”

Next winter, the migratory birds will head south and repeat the process over again when the warm weather returns, Islam said.

As for the Cardinal, the state bird of Indiana has smaller migratory patterns that allow for it to stay in the same area year round, Rose said.

Contact Chase Martin with comments at cgmartin@bsu.edu.