Months of racial controversy and requests for the removal of former president Tim Wolfe at the University of Missouri were met fewer than 48 hours after the school’s football team took a stand.

Several black players on the Missouri football team decided on Nov. 7 they weren’t going to play unless Wolfe resigned, following accusations of inaction regarding racial tensions. And the Tigers’ head coach, Gary Pinkel, stood with his players.

Ball State looks at its own progress on diversity after events in Missouri. Read our coverage here.

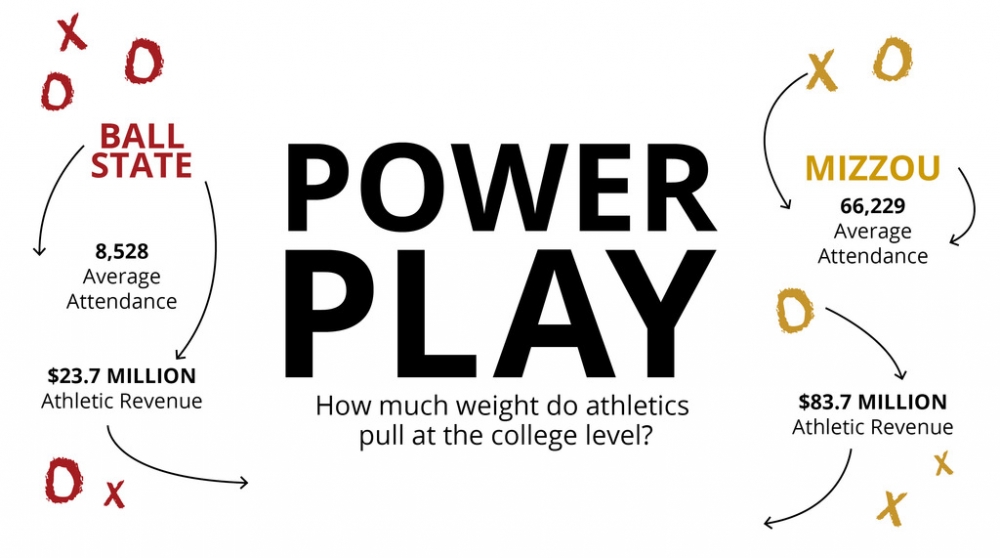

Missouri plays at an elite level in the Southeastern Conference — it’s a much larger scale than Ball State in the Mid-American Conference, but it bears the same question: How much weight do athletics pull at the college level?

Short answer — a lot.

“The questions and the issues that were brought to light were obviously very important,” Ball State Athletic Director Mark Sandy said. “But when the football team and other student-athletes on campus were willing to support the ideals of their fellow students, it certainly brought more national attention to the issue.”

Follow the Money

A matchup with Brigham Young University on Nov. 14 was the first game on the schedule that the team’s decision threatened.

Not playing against BYU would have hurt more than just Missouri’s image. Missing games at the collegiate level means breaking contracts between the competing schools, and boycotting this particular game would’ve resulted in a $1 million compensation to BYU.

Athletics play a big role at any university in part because of the money the different teams collectively bring in.

University of Missouri athletics pulled in $83.7 million in revenue in 2014, according to USA Today.

Losing $1 million from the BYU game would have an effect on Missouri’s athletic income, but to Ball State, which made just $23.7 million from athletics in 2014, the same $1 million penalty for not playing would be more crushing.

There are several monetary costs that make up a school’s athletic revenue, such as TV deals and ticket sales. But missing a game would extend far beyond the money.

“The actual monetary cost is one thing,” said David Ridpath, an associate professor at Ohio University and co-editor of Journal of Issues in Intercollegiate Athletics. “I think it would be greater than a million dollars, if not more. The actual public relations loss would be immeasurable.”

Missouri’s athletic revenue is produced directly through sports and what they bring in. For example, ticket sales make up well over a fourth of the total revenue for the year. In home football games this season, the Tigers are averaging 66,229 fans per contest.

On the contrary, Ball State is averaging 8,528 fans per game.

To make up for other areas, more than half of the 2015-16 Ball State auxiliary fund budget for athletics comes from a student services fee, which students pay in addition to base tuition. Missouri doesn’t collect any money from a student services fee.

Missouri ranked No. 32 out of 230 schools in the country in net revenue last year, while Ball State was No. 112. Despite the discrepancy between the schools’ budgets, the money they bring in through athletics is important to each school.

“There is a power that the student-athletes have,” said Terry Hutchens, a sports reporter who has covered Indiana University basketball and football for 18 seasons. “All you ever hear about is how the athletic department is making all of the money.”

Ball State took on one of Missouri’s conference rivals this year in Texas A&M at College Station.

The Cardinals were paid $1.2 million to play in a game in which they trailed 49-3 at halftime. In a situation where Ball State would’ve missed or boycotted the game for any reason, the university would’ve had to pay Texas A&M $1 million in compensation.

Ball State pockets $1.2 million for Texas A&M game

A $2.2 million swing for not playing Texas A&M would’ve impacted the school’s athletic revenue, completely eclipsing the school’s expected $1,900,000 in guaranteed game revenue for next year.

Sandy said he didn’t think the money Missouri would’ve had to pay for missing the game in itself played a role in former President Tim Wolfe’s resignation. The Tigers paid $250,000 for BYU to come play them at Arrowhead Stadium, and they would have had to play an additional $750,000 if the Tigers boycott had continued, according to Darren Rovell of ESPN.com.

For a school that makes a lot of money from athletics, missing the game wouldn’t have too much of a strain on Missouri’s athletic budget.

Missouri’s stand against its president was something of rarity, and it was felt in more ways than just its potential impact to the athletic budget.

“I think it shows the power that athletes have, not only to bring attention to social activism, but also enact change,” Ridpath said.

Impact of Athletics

Ball State may play in the MAC, but that doesn’t mean it isn’t familiar with the national stage on which Missouri stands.

In 2008, the Cardinals had an undefeated regular season and were ranked as high as No. 12 in the country before losing in the conference championship game. Years later, Ball State was one of the top teams in the conference with now-NFL players Keith Wenning and Willie Snead.

If an issue like this were to arise at Ball State, it might not dominate the national conversation like at Missouri. But Sandy said an issue like racism could have a big impact at any university if there is a group on campus that is passionate about it.

“I think what would happen is — at any institution, no matter its size — if there are serious issues that are brought to light by faculty, staff or students, people need to pay attention to what people are saying and what the issues are that are important to them,” he said.

Because sporting events are often televised — football in particular — athletes typically become the faces of the university for which they play.

Intra-conference competition in MAC football is featured on ESPN networks during Tuesday, Wednesday and Thursday night games. This is an opportunity for the conference to play in “prime-time,” because Power-5 conferences run the bigger cable networks on Saturdays.

While football has been prominent at Missouri for years, a recent conference shift brought the Tigers to a new level on the college football food chain.

As of July 2012, the Tigers joined the SEC — a conference that dominated the nation in bowl game revenue last season. The ever-expanding SEC Network covers every sport in the conference, which features four teams currently ranked in college football’s AP Top 25.

An athletic team using its power to influence a decision is historically pretty rare. Missouri’s national prominence further highlighted the issue, along with the decision of the coaching staff to stand behind its players.

Sandy said athletes should be aware of social issues and think for themselves. And when they do take a stand, others should want to be as supportive as they can.

It’s all part of a life lesson, he added.

“I think our coaches are very much supportive of the student-athlete experience,” Sandy said, “and they would stand behind our student-athletes on issues that were constructive and were sending a certain type of message. I think they would, yes.”