At the Dance Marathon, Jackson Berry shared his story of recovery after a Traumatic Brain Injury. He said he hopes to help others understand the importance of protecting the head.

- A Traumatic Brain Injury can lead to wide-range of short- or long-term issues affecting cognitive function, motor function, sensation and emotion.

- Approximately 3.5 million Americans are living with a TBI-related disability.

- Among all age groups, motor vehicle crashes and traffic-related incidents result in 31.8% of TBI-related deaths.

- The CDC offers multiple education and awareness efforts including: seat belts, motor vehicle safety, sports and recreation safety, violence prevention and fall reduction.

Senior Jackson Berry is 21, in a fraternity and he’s got a dream for his life. But almost five years ago, Berry suffered a severe brain injury, needed multiple medications to get through each day and spent six weeks in intensive rehab after losing proper function of his mind and body.

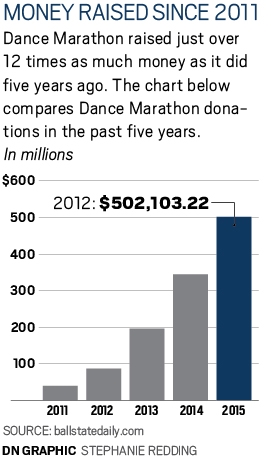

Jackson and his parents, Bob and Diane, were just one of the 11 groups with connections to the Riley Hospital for Children chosen to speak at the Ball State Dance Marathon Saturday. The marathon raised $502,103.22 for programs at Riley Hospital, surpassing this year's goal of $500,000 and exceeding last year's donations by $157,302.01.

The accident

In July 2010 Jackson was just 17 years old and enjoying his time at summer camp when he and his friend had a waterskiing accident. They weren’t wearing helmets.

After the incident, other campers and counselors brought him to shore. Berry was unable to use the waiting ambulance. Instead, a helicopter brought him to South Bend Memorial Hospital to be stabilized.

There, medical professionals discovered the extent of Jackson’s injuries: severe brain trauma to his frontal lobe, two collapsed lungs, a chip fracture in his left femur and a fractured clavicle. Jackson doesn’t recall anything from that day; he only has firsthand and eyewitness accounts to lean on.

After being airlifted to Riley Hospital for Children, he spent 10 days In a comatose state, followed by weeks of physical, speech, and occupational rehabilitation. He also needed tutoring to keep him caught up on schoolwork.

“My brain became a skeleton of what it used to be,” said Jackson, recalling his condition.

Jackson’s mom Diane compares his mind to a computer constantly needing to be rebooted. On the day of the accident, Diane happened to be off-work. The camp nurse called and said there had been an accident.

“Those are the worst words you can hear,” said Diane. “I asked if he was awake and she said no. I’m an ER nurse. I know that means it’s bad.”

Jackson’s dad Bob rushed home early from work to wait with Diane until they found out where they needed to go.

“We took it a minute at a time, not knowing,” he said. “But there was no point sitting around at work.”

The recovery

According to his parents, Jackson has a trademark of lifting one, then both eyebrows to get a laugh out of people.

In the hospital, Diane would whisper to him, “Jackson, do the eyebrow thing.”

He would.

“It was our first indication he was still with us,” said Bob.

Today, Jackson makes light of his parent’s emotional memory.

“I had a trick that my parents could show off. I was on display,” he said playfully. “But when I was depressed, it helped me. I’d do that, and I could feel it in my forehead and remember the laughter. It made me feel better.”

After the immediate danger of Jackson’s injury passed, his brain damage continued to affect him.

Jackson dealt with serious bouts of depression, contemplation on suicide and manic episodes. The traumatic injury to his frontal lobe had removed all sense of inhibition.

“I was in denial,” said Jackson. “I thought I could run and jump and play with my friends.”

Then there came what Jackson has proudly titled “The Moment in March.” At the time, he was in a deep manic stage.

“I felt on top of the world. Think temper tantrum meets road rage,” he said.

But on the way home from school, Jackson abruptly decided it was time to stop making excuses for himself.

“I stopped blaming the accident and started living my life," he said.

And that’s just what he did. He still experiences some of his issues, but Jackson graduated from high school, on time, with a higher GPA than he had ever had previously.

The activist

Jackson enrolled in Ball State in 2011, and plans to graduate with the Spring 2016 class with a degree in health and physical education.

His decision to go into that field was partially related to his accident.

“I had some phenomenal teachers reach out to me and I knew I wanted to do that. I wanted to have that impact,” he said.

He pledged Sigma Chi, who modified their pledge system to accommodate some of his specific needs.

“It’s hard being a college student and saying I have to go to bed at 10 o'clock or I don’t drink,” said Jackson. “They were there for me.”

Bob said their story is a testimony to the quality of doctors at Riley.

“They didn’t just pass him off,” he said. “There was no reason not to pursue every possible avenue.”

As for being a part of Dance Marathon, Jackson couldn’t be more pleased. He's participated before.

“I’m so honored I was able to speak at this and share the story that’s so dear to me. I’ve been looking forward to this since the day after it last time," he said.

One of his biggest goals is to help others understand the need to protect themselves.

“We need to wear helmets and we need to wear seat belts. We need to protect our heads. We only get one and I’m so glad I’ve still got mine,” he said.

Humor and positivity get Jackson and his family through each day.

He still has that sense of humor that shone through even while in the hospital.

“My frontal lobe injury now manifests itself in the form of terrible, terrible jokes. They don’t even make sense sometimes. But look at me, look at what I’ve been through, how far I’m come. How far I’m gonna go,” he said.

Nothing is going to hold Jackson Berry back.