“Student Evaluations of Teaching (Mostly) Do Not Measure Teaching Effectiveness,” published by ScienceOpen, tested both American and French university students and analyzed their final grades along with opinions of their either male or female professor.

At the French university, students took the same course from different male and female professors, but took the same finals at the end of the courses. Though students who took the course from the female professors received slightly better grades overall, the male professors were rated more highly by male students.

At the U.S. university, half of the male and female professors involved in the study agreed to dress as the opposite gender throughout their entire online course. At the end of the course, female students rated the professors they believed to be male higher overall.

Some Ball State students acknowledged the possibility of a gender bias against female teachers.

Katy Volikas, a sophomore international political science major, said she thinks male and female professors are critiqued differently by their students.

She said on ratemyprofessors.com, she sees more "attacks" on a professor's personality within a rating – rather than their course material – if that professor happens to be female.

"They may be called rude … or worse," Volikas said. "Where for males, it's a question of, 'do they give extra credit or not?'"

Rachel Miller, a junior nursing major, has had primarily female professors for her classes, with very few male students. She had similar things to say about her professor's ratings.

"[Females] might get called an ice-queen, but guys are [called] unproductive or monotoned."

Miller said she believes this might be because of social expectations and gender roles. Where females are expected to be "friendly and accommodating," males typically are not.

But Jacob Freske disagrees. The senior telecommunications major said that while most of his professors are male, he has had equal respect for his female professors.

"I look at professors as people that know their field, their area of study," he said. "They're here [at Ball State] because they're good at what they do."

Miller said she always does evaluations, but sees them as "busy work" and just more to do during finals week. She said she doesn't give her honest opinion on them, either.

"You just don't know where it goes, what happens, after you submit them," Miller said.

Some Ball State professors agree that there may be gender biases, but they are generally more concerned with other aspects of the teacher evaluation process.

Martin Wood, an associate professor in the Department of Physiology and Health Science, has been teaching at Ball State for 21 years.

Along with teaching and keeping up with his own evaluations, Wood has served on the College Promotion and Tenure Committee for his department. This role has him thoroughly reading other professor's evaluations – both male and female.

While he said he hasn't recognized any gender bias in the evaluations that he has read, he doesn't doubt that one might exist.

"There were both female and male professors that had low ratings. I honestly don't really think I noticed any difference," Wood said. "But it's in our culture, it's traditional."

As another tenured professor, his evaluations have a bearing on his salary and career at BSU. Because of this, he said he both pays attention to comments student write about him and also makes changes to his courses based on what they say.

Still, Wood doesn't entirely trust the current evaluation system because it isn't required for students to fill them out.

"I think we all – I hope we all – recognize that when it's not mandatory, it's not accurate," Wood said.

When Wood started teaching in 1994, he said he remembered response rates of 90 percent for the evaluations.

"Now we're lucky if we get 50 percent," Wood said.

Holly Dickin, an instructor in the Mathematical Sciences department, said she can't say for sure if she experiences a bias because of her gender because she only sees her own evaluations.

However, she said that she and male professors – or any other professor – are different people and can't be compared accurately.

"They're going to be different. I can't say it's because I'm either male or female," Dickin said.

Her concern, rather, is students picking and choosing which professors to evaluate, which she said would cause inaccurate data from evaluations.

"It's typically the students who love you and hate you who fill them out," Dickin said.

Student comments are important to Dickin, and she said she wants more students to do their evaluations.

"It's really good [when] students fill them out, I ask them every semester – beg them, but the reality is they're not all gonna do it," she said. "In my large classes, I'm good to get half of them."

While Dickin said she does her best to change things in her course for students, it's hard when comments aren't specific or helpful. She said students might not be specific because they don't think the evaluations matter or are taken into consideration with administration, but she wishes they would be because professors should care what their students say.

Larry Riley, an instructor in the English department, has been teaching at Ball State since 1992. He has served on the department's Merit Committee to choose other instructors to receive merit pay based on their evaluations.

Each English instructor, including Riley, must complete an annual report with information derived from their evaluations. While they must present their numerical scores, they also have to write an analysis about comments from students.

While serving on the Merit Committee, Riley read many evaluations from male and female professors in his department. He said he saw no evidence of a gender bias.

"If I would think back, my guess is, as a committee, we had pretty equal numbers for people we recommended for merit between the sexes," Riley said. "I definitely never noticed lower ratings for female teachers."

But Riley sees other room for error with the current evaluation system. He said he doesn't think students have the ability to accurately critique their professors directly after their time with them in the classroom.

Instead, he argued that years after completing a course, students would be able to see if a professor was effective in their teaching or not.

"That's a better time, I think, to assess than the last day you have them for class," Riley said. "What did they learn? What did you do? Did it help you?"

Riley uses this method himself, simply by emailing his past students and asking them how — looking back — they recall the course.

"I will say that, occasionally in the past, I would email, let’s say in August of a school year, students I had maybe three years earlier. I would ask them about what they've done and what could have been done differently."

He said he knows no method for evaluating professors is perfect, but he finds this effective to help his teaching.

Shaheen Borna, a Miller College of Business marketing professor, has been at Ball State for more than 34 years. He recalls when students completed their evaluations in class with a paper and pencil.

While he said doesn't believe there is a gender bias with the evaluation system, he does think that there are other types of inaccuracies that come along with the way the university currently does evaluations.

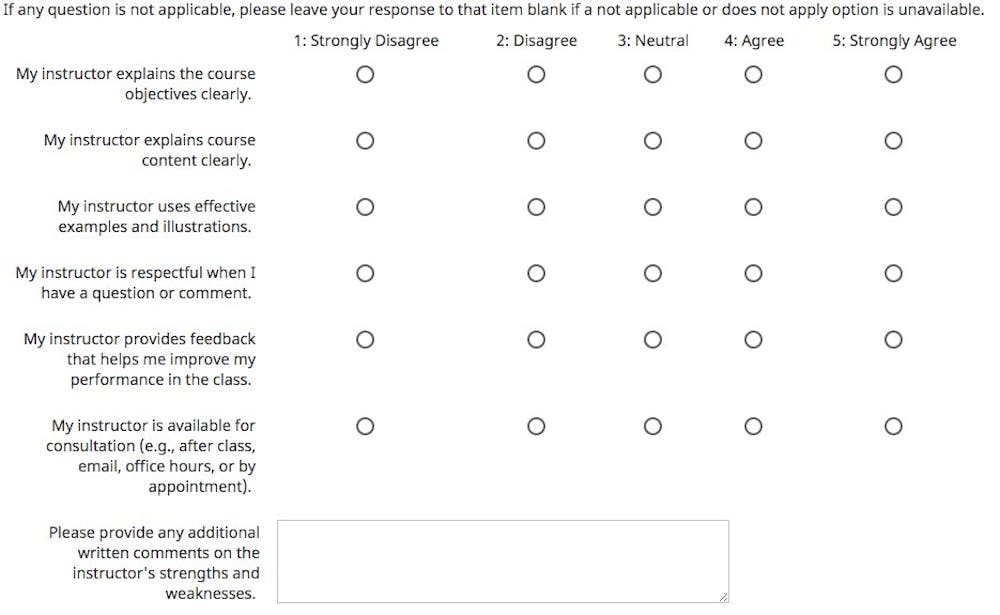

"The [evaluation] questions ask students about teacher effectiveness, but what is teacher effectiveness?" Borna said. "We don't know it, students don't know it."

He said that he wondered, with the questions the evaluations currently ask, if the university is really measuring what it’s supposed to be measuring.

Borna said he believes that there is a bias – but not against a professor's gender. It's a bias from only certain students completing their evaluations and students not understanding the questions.

Because in many cases only unhappy students do evaluations, he said they can’t be valid.

Even with this belief, Borna still takes the time to read what students say about him. If he didn't, his job could be affected.

As a tenured professor, not only evaluations, but also service and research affect Borna's salary and position with the university. Though his evaluations could affect him, he said they never have.

"My [evaluations] are not bad," he said. "I'm good, but [my evaluations] aren't actually a measure of that."

But he does get his share of negative evaluations.

"I push my policies, I get bad evaluations," Borna said. "If you don't come [to class] I'm going to reduce your grade. But students don't like that."

When a professor gets one or several negative evaluations, Borna said that he doesn't think the university can take any valid data from them.

"It's impossible," he said. "To be fair with the university, they can't know the cause of that [negative evaluation]."