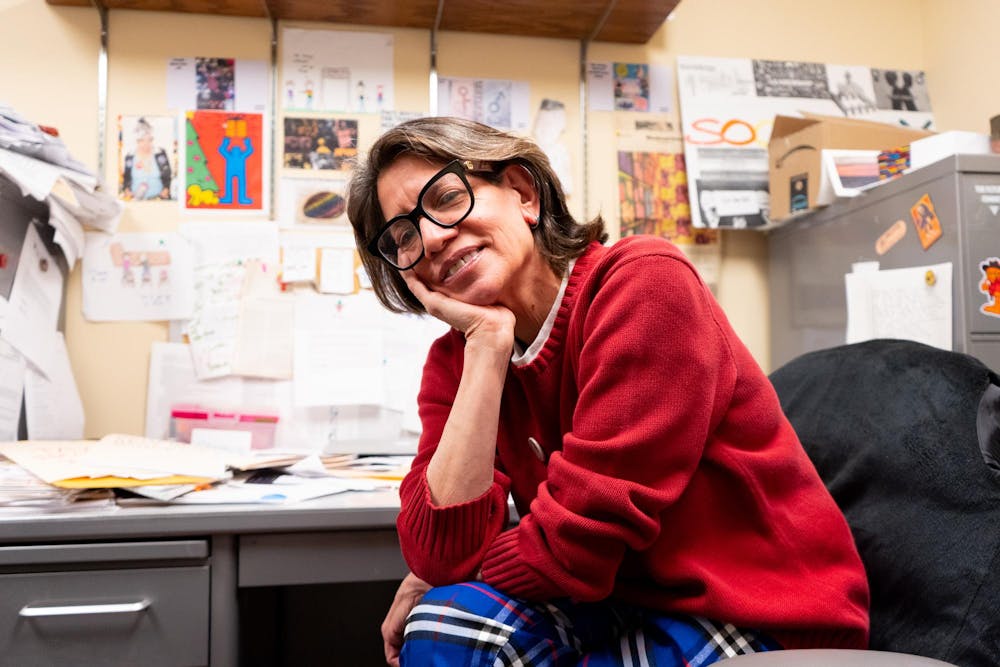

Within the narrow, beige hallways of Ball State University’s North Quadrangle Building is room 215, the office of Sara Collas, an assistant teaching professor of sociology.

Collas’ office, live with the color of artwork and thankful, calligraphic inscriptions from former students, is a reflection of her artsy clothing style with chic plaid influences and the bright, big-toothed smile and warm handshake she offers when meeting someone new.

“I learned at a young age that color travels, and I thought, ‘This is the most exciting concept I've learned.’ I still use that concept. I love using color in my own self expression,” Collas said.

The concept came from a lesson at the Cleveland Museum of Art, which Collas attended in the company of her twin sister as a result of their mother’s strategic planning.

“Even though we were poor growing up, she was able to navigate ‘the system’ and get these scholarships for different, very middle class programs, like art lessons at the Cleveland Museum of Art,” Collas said.

Various lessons about the vitality of art and culture at a young age shaped her, and the lessons extended at home. Collas said her mother — who died last year at age 92 — was not only “a great Jewish storyteller,” but also, “the most influential person in my life,” with enough chutzpah, or audacious self-confidence, to travel the world independently, well into her 80s.

“My mom instilled a lot of confidence in me,” she said. “My mother always told me how beautiful I was, how smart I was [and] how special I was. I remember she always told me what a beautiful smile I had, and she thought one of the Kennedys would ask me to marry him because I had such a beautiful smile.”

Though Collas does not have children with a Kennedy brother — much to the dismay of her mother — today at age 61, she has found a way to honor her Jewish heritage in the absence of her mother from an opportunity provided by Ball State and Dr. Galit Gertsenzon, an assistant teaching professor at the university’s honors college.

Gertsenzon hosts a variety of Jewish studies workshops upon taking the directorial role of the university’s Benjamin and Bessie Ziegler Jewish Studies Program in 2022. The intention behind those workshops, she said, is to provide the university and surrounding community with an understanding of, and appreciation for, Jewish history, culture and faith.

The presentations and revitalization work she has done for the decades-old program have left a lasting impact on colleagues and staunch proponents of the Jewish studies program like Collas, who has invited Gertsenzon to speak to her Music and Art in Society class.

“Dr. Galit is an amazing writer, scholar, teacher and musician. Ball State University is so fortunate to have Dr. Galit here,” Collas said.

Although Gertsenzon wears many hats, her favorite is educating younger generations by helping them nurture their passion for music.

“I love music. I cannot see myself doing anything that doesn't involve music,” she said.

Her affection for rhythm and sound was fueled by a relentless desire to play the family’s piano like her older sister. The then envious six-year-old stubbornly begged her parents for piano lessons.

At the time, Gertsenzon said her parents “had no money,” but after two years, her grandmother was able to find a “very good” teacher whose price rates did not add to the family’s already-existing financial burdens.

Nearly two decades later, Gertsenzon was an intrinsically skilled pianist but had yet to grasp the mechanics of musical composition until graduate school, where she was introduced to — and entranced by — the work of Gideon Klein, a Czechoslovakian pianist and classical music composer in the early 20th century.

“The more I studied and played the music, I found there is so much more music that is unknown, even to this day,” she said.

That realization sparked a desire to know the unknown in all her endeavors, including that of her heritage, making her a lifelong learner and passionate educator.

Now, outside of her work at Ball State, Gertsenzon, teaches private piano lessons to eager children like she once was.

“I see so much growth in the kids that I teach, and I have the privilege to become the music mentor. It's the greatest gift I can ask for in professional work, to be someone who's educating others,” she said.

When it comes to Jewish faith, Gertsenzon is disheartened by a growing number of Holocaust deniers across the globe. Her sentiments were echoed by Collas who has noticed an increasing amount of anti-semetic behavior, particularly on college campuses.

A January 2025 worldwide report from The Conference on Jewish Material Claims Against Germany (Claims Conference Organization) detailed that nearly half of all U.S. adults (49 percent) reported Holocaust distortion is “common,” with 38 percent of the country’s adults flatly denying it.

Those numbers, Gertsenzon said, are a byproduct of social media intake — particularly among millennials and Generation Z — which is creating a media literacy deficit.

“A lot of people now are getting their information from social media, and [social media] is based on other people's opinions, not facts,” she said. “The Holocaust did not happen in one day. It happened as a series of very small steps.”

The same Claims Conference Organization report highlighted the more than three-quarters (76 percent) of U.S. adults that believe something like the Holocaust could happen again today.

“History tends to be forgotten. History repeats itself. The Nazis did not seize power — they were elected. There were people who wanted them in power, and as soon as they took power, they abused the power to discriminate and murder millions of people,” Gertsenzon said, adding that amid all the questions, uncertainty and polarized political climate nationwide, “Education is the answer.”

Collas has been attending Gertsenzon workshops since last summer and has been “blown away” ever since.

“I had always thought about the Holocaust in terms of all the people that were killed, the millions of people. I thought of death. I thought of despair. I thought of tragedy. I had never thought about music and art during the Holocaust,” she said.

Gertsenzon’s breadth of knowledge relating art and music to the Holocaust comes from a class she’s spearheaded since 2018 through the honors college.

The course, though previously offered only online, will now be offered in person and branch out to encompass not just the Holocaust, but the artistic influences of WWII as a whole. Gertsenzon said the inclusion is intended to illustrate the quantity of minority groups that were persecuted by the Nazis.

Collas, a member of multiple minority communities, including LGBTQ+, learned a common thread when it comes to the necessity and durability of diverse storytelling.

“One thing I learned in the Jewish storytelling workshop was how all oppressed groups use humor to deflect our pain, our struggles [and] our hardships,” she said.

Collas’ eye-opening lesson of humanitarian commonality reflects Gertsenzon's mission for the Jewish studies program and its sister workshops and classes.

“My goal as an educator is to teach about things that happened. If my family didn't survive, I would not be here,” Gertsenzon underscored. “They survived. I have family members who died in the Holocaust, and I have family members who survived, and thanks to them, I'm here,” she said.

Contact Katherine Hill via email at katherine.hill@bsu.edu,