1989.

The year might bring images of big hair, Madonna, Michael Jackson or the last years of the Cold War. However, beyond these popular cultural moments, it is also the year when Kimberlé Crenshaw, a young Black woman, wrote a paper titled, “Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics” that introduced the term “intersectionality.”

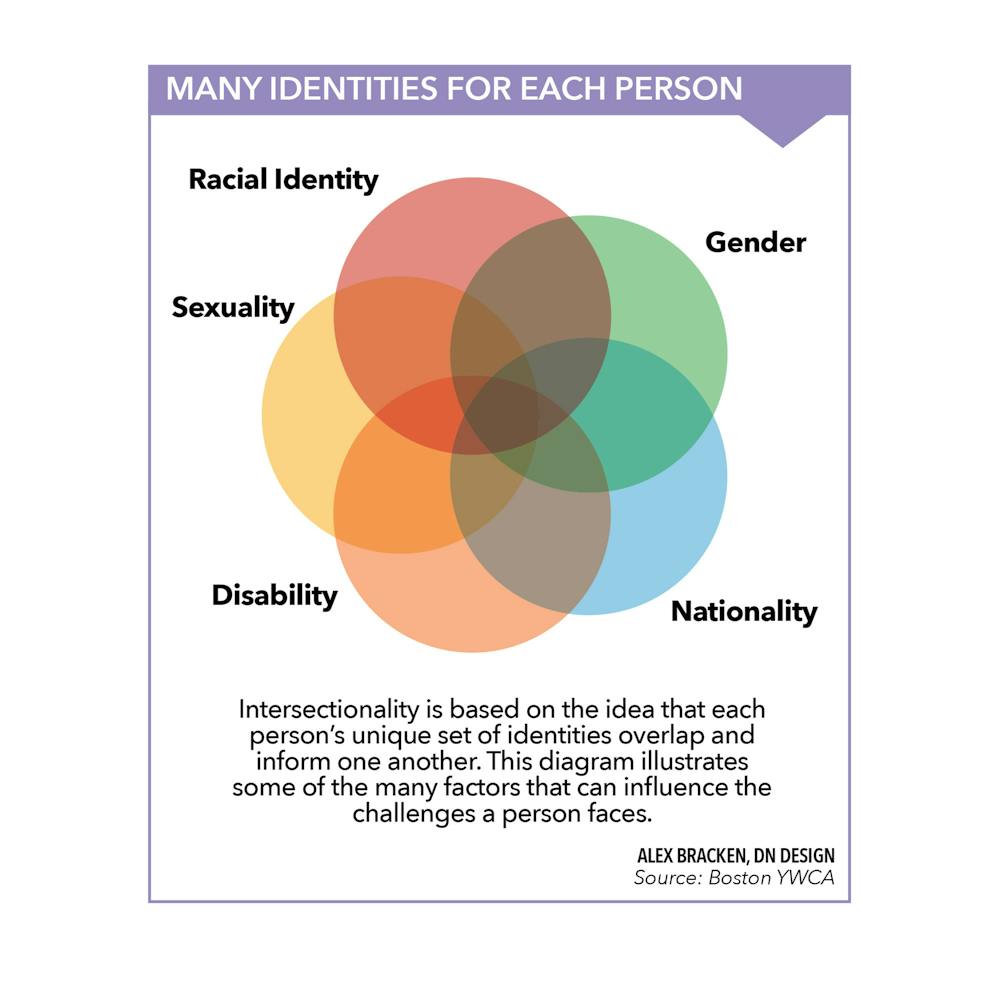

Merriam-Webster defines intersectionality as “the complex, cumulative way in which the effects of multiple forms of discrimination (such as racism, sexism and classism) combine, overlap, or intersect especially in the experiences of marginalized individuals or groups.”

Emily Rutter, associate dean of the Ball State University Honors College and associate professor of English, recognizes how the foundation of the United States is based on racial stratification. She said when it comes to imagining women, the default is typically a white woman, even though there is diversity among women in the U.S.

“Intersectionality, in the conversation about gender, feminism or women’s empowerment, helps us remember that there is no universal woman’s experience,” Rutter said. “Intersectionality, along with other terminology and other kinds of complexities, helps us remember that there’s all kinds of experiences of being a woman.”

Rutter is the faculty adviser for the Student Anti-Racism and Intersectionality Advisory Council (SAIC). The group was created by Rutter and students in March 2020.

Rutter said she and the students originally planned SAIC to introduce a course centered around anti-racism and the relationship between racism and sexism, but the group grew to be more than a course.

“It blossomed into many other things— events, educating [the] community and students and providing resources online,” Rutter said. “We also planned the class, which is now part of the African American Studies curriculum, it’s called AFAM 150: Understanding race, anti-racism and intersectionality.”

Rutter and the SAIC are not the only ones thinking about intersectionality.

The 26th annual Student History Conference, organized by the Ball State Department of History, held a panel Feb. 2 titled “Intersectional Identities in Modern History,” where presenters shared papers about the stories of a diverse range of women throughout history.

The papers explored stories of women of color throughout time and through a variety of spaces: day-to-day life, film, revolution and more. The papers featured works from several students such as one by Ball State graduate student Emily McGuire’s, “1939’s Gone with the Wind: Gender & Race in the Symbol of Southern Mythology,” and another by University of Illinois-Chicago graduate student Katy Evans’, “El hombre hacer valer a la mujer: The Perception of Women and Their Participation in the Revolution.”

Another presenter was Madeline Mills-Craig, fourth-year history major, who wrote a paper titled “Tiger Women: Analyzing the Chinese American Women Experience in Western United States from 1850-1885.” Mills-Craig is an Asian studies and Chinese minor, inspiring her to research Chinese history. She said there were few documents for her to study because of how few Chinese women immigrated to America.

“One of [the Chinese woman’s] biggest hardships was trying to find their place in society,” Mills-Craig said. “As foreigners, they weren’t really seen as the typical wives … or real [women]. A lot of times women were brought over illegally and used for prostitution.”

Mills-Craig said her studies connected to intersectionality due to how the Chinese women were viewed by the people around them. She said they had the “worst of both worlds” because in America, due to both their ethnicity and gender, Chinese women, similar to other women of color, had to face double the hardships compared to white women at the time.

Mills-Craig said the intersectionality issues women of color had to face in the past are still relevant, but people tend to not acknowledge these issues.

“Intersectionality is one of those topics that a lot of people will gloss over,” Mills-Craig said. “It is such a big barrier minority [women still face today] ... writing a paper on these double barriers could be even more relevant.”

Delaney Fritch, fourth-year majoring in history and political science, also spoke at the panel. They recognized how queer history primarily covered white people who identified as queer. Fritch said when there is research on the queer community, it is usually centered on white people.

Fritch came to the idea for the research after spending time in classes with Charlie Geyer, assistant teaching professor of Spanish, and Emily Johnson, associate professor of history. In a class with Geyer, they were able to read the work “Borderlands,” also known as “La Frontera,” by Gloria E. Anzaldúa, which introduced them to the complexities of Chicano culture. In their simultaneous class with Johnson, they said they were given the opportunity to see stories of how whitewashed queer history was. They said both professors had influential roles in the inspiration and development of the research process.

In their paper, Fritch researched the idea of sexuality intertwined with the Chicana identity.

“They all identify as lesbians, and they all identify as Chicanos, and I guess you could also say they all identify as women,” Fritch said. “However, that doesn’t necessarily mean that their experiences are remotely the same. While there is overlap between them, they are quite distinctive.”

Fritch explained the Chicano movement was a group of both men and women, but it began to segment, as members of the group felt it was not recognizing issues of patriarchy. Eventually, the members of the group formed new segments such as the lesbian Chicana movement.

Fritch discussed the importance of using the term intersectionality when people have discussions of women and others throughout history and modern day.

“Intersectionality allows us to paint a clearer and more accurate picture of people’s lives,” Fritch said. “Without intersectionality, we are simply skimming the surface of any group; it’s needed to understand the complexities.”

Contact Abigail Denault with comments via email at abigail.denault@bsu.edu. Contact Maya Kim with comments at mayabeth.kim@bsu.edu or on Twitter @MayaKim03.