Kate Farr is a first-year journalism major and writes “Face to Face” for the Daily News. Her views do not necessarily reflect those of the newspaper.

I grew up in a town of less than 1,500 people.

The most excitement my hometown, Antwerp, Ohio, gets is the high school basketball team being runner-up at state, a car show every July along Main Street or a community potluck put on by one of the four churches in the 1.33 square mile area.

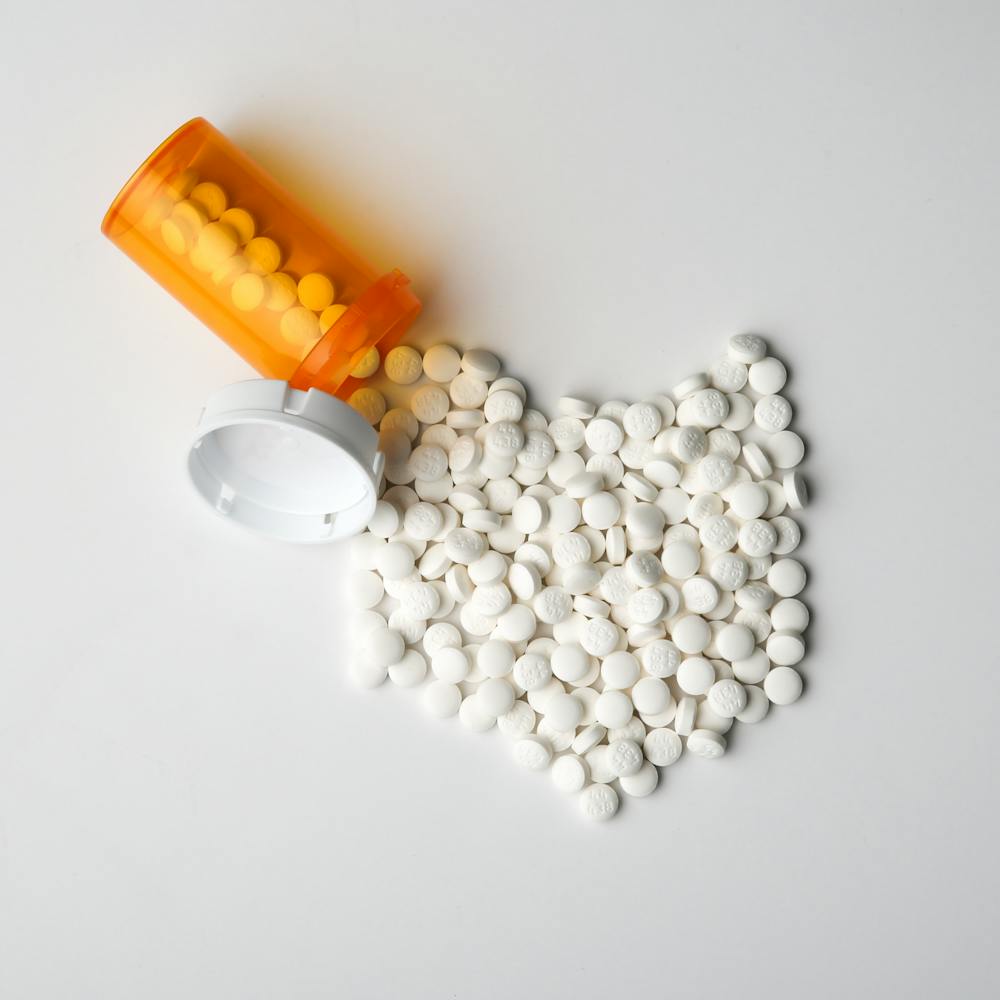

My hometown, like many others in the Midwest, is a place defined by little commotion, conservative ideals and opioid addiction.

As I got older – getting into the territory of middle school and high school – I became aware of just how many kids in my community were living below the poverty line, dealing with parents and family members addicted to painkillers and wondering if there would be dinner on the table that night.

Since the 1960s, the Appalachian region, where many of my community hail from, has experienced a socioeconomic rut that has caused widespread poverty, rising mortality rates and discrepancies ranging from flawed healthcare systems to income inequality, according to the Appalachian Regional Commission.

While ventures from agricultural expansion to coal mining allowed for industrial inclination up to the mid 20th century, Appalachian communities throughout the Bible and Rust Belts – terms used to describe these regions of de-industrialization and Protestant Christian dominance – have slipped into a state of economic and moral decay as industries left, education funding weakened and more individuals became stuck in blue-collar jobs where, more often than not, wage growth lagged behind productivity growth.

Many of the common labor-intensive professions held by lower class Americans led to rises in medically prescribed opioids, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), thus fueling a long-term and generational addiction throughout crumbling communities in middle America.

The period of de-industrialization in the 1970s, as well as the 2000s and onward, has found many blue-collar workers without jobs. Thus, like many other towns existing within or bordering the Appalachian region, Muncie has seen its fair share of foreclosed factories, businesses and neighborhoods. Currently, the city’s poverty rate is 30.2 percent of the total population, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.

That’s almost 20,000 people.

Even as Appalachia has experienced a worsening economic lag over the past half century, little has been done in terms of domestic politics to lift the region from a trough of poverty, inequality and abuse.

That is where J.D. Vance comes in.

According to his memoir, Vance was born into an Appalachian transplant family settled in southern Ohio. Starting at a young age, he became acutely aware of the opioid addiction, domestic abuse and poverty that afflicted his loved ones. In an attempt to break the generational ties of his hillbilly roots, Vance became one of the few to rise up the socioeconomic hierarchy. Vance served in the military, graduated from Ohio State University and Yale Law School, wrote a bestselling memoir – Hillbilly Elegy – that later became a film adaptation starring Glenn Close and Amy Adams, and was nominated as Ohio’s Republican party nominee in the Senate election for this November.

As a long-time Republican, Vance was reported to have considered a bid for the U.S. Senate in 2018, running against Sherrod Brown (D-OH), but declined to run. However, with the retirement announcement of Rob Portman (R-OH), Vance expressed an interest in running with the Republican seat being vacated. In July 2021, he officially entered the race for the Senate.

Within the pages of Hillbilly Elegy, Vance focused on the effects of poverty and addiction, social immobility and economic inequality. In his political promises, Vance reiterated the main point made within his memoir: politicians must provide a vehicle to increase economic and social mobility, thus pulling Appalachian and other lower class Americans out of poverty and the grips of the opioid epidemic.

In fact, following the 2016 presidential election, Vance founded Our Ohio Renewal, a nonprofit charity that is, as stated by the charity’s Twitter profile, “dedicated to promoting the ideas and addressing the problems identified in J.D. Vance’s Hillbilly Elegy.”

However, the organization was shuttered in 2021.

According to state records obtained and reviewed by the Associated Press, Our Ohio Renewal was shut down following Vance’s win in the Republican primary.

The group’s website and Twitter account quickly became inactive. Vance’s campaign didn’t provide any documentation on the project itself. The Ohio Democratic Party eventually bought and revamped the old site – renaming it “Our Ohio Ripoff” – and used it to expose how the non-profit didn’t actually spend any of its funds on the opioid epidemic it was meant to be fighting.

One of the more noteworthy efforts for the organization was sending an addiction specialist for a year-long residency in Ohio’s southern Appalachian region. But this is where things get fuzzier.

An AP review reported the presence of ties between this addiction specialist, Dr. Sally Satel, and Purdue Pharma – the manufacturer of OxyContin. OxyContin, a highly addictive opioid, is still manufactured, prescribed and distributed in the United States.

There are countless ethical dilemmas in Our Ohio Renewal allowing for the employment of a doctor directly connected to Big Pharma. Vance said he wasn’t aware of this connection but remained “proud” of her work in treating patients, according to a statement by the campaign.

While the organization was well intended, its closure sheds light upon the shortcomings of possible political candidates.

Vance’s failure in fulfilling the promises he made on his journey to obtaining the Senate nomination has shown a lack of commitment in addressing the opioid crisis.

Lower-class children are burdened with psychological damage after living in trauma-conducive homes and opioid-plagued communities, according to the statistics on Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) provided by the CDC.

America’s working class is often hit harder in natural disasters and health emergencies because of uncertain living conditions or limited access to affordable health services.

During the summer of 2020, 60 percent of those residing in West Virginia alone said they were at risk of homelessness, especially those struggling with addiction, according to a study by the West Virginia Center on Budget and Policy.

Approximately nine percent of Indiana families are currently living below the poverty line based on 2020 statistic from Stats Indiana

While community programs and some government funding have lessened the load of crippling poverty in the region, it is impossible to begin the rehabilitation in Appalachia without addressing the underlying causes. Through recognition, proper funding and political progress, the United States holds the potential of eradicating a larger portion of the American underclass.

If Vance is to secure a Senate seat for the state of Ohio, I hope he seriously works to enact policies that address the opioid epidemic, and after cutting ties with Big Pharma, I’d like to see him revive Our Ohio Renewal in aiding specific Appalachian communities.

I did not grow up in the same strained, familial environment as Vance. I’m not a product of divorce. My parents weren’t stuck in relationships riddled with drug usage or domestic abuse. I never observed any sort of violence between family members.

But I saw it. It coursed through the veins of my community.

I saw what opioid addiction could do. I saw the shaking, tremors and slurred speech. I saw my friends whose parents were laid off and couldn’t afford the Lunchables that many of us had in our lunchboxes. I saw the countless businesses that moved onto the mostly desolate main street – floundering and failing before the end of the year. I saw how hillbilly transplants and middle Americans felt left behind in political endeavors.

It’s not just about scoring political points off of the suffering of Americans. It’s focusing on limiting America’s demand for these drugs, regulating the drug trade and rehabilitating those afflicted.

Contact Kate Farr with comments at kate.farr@bsu.edu or on Twitter @katefarr7.