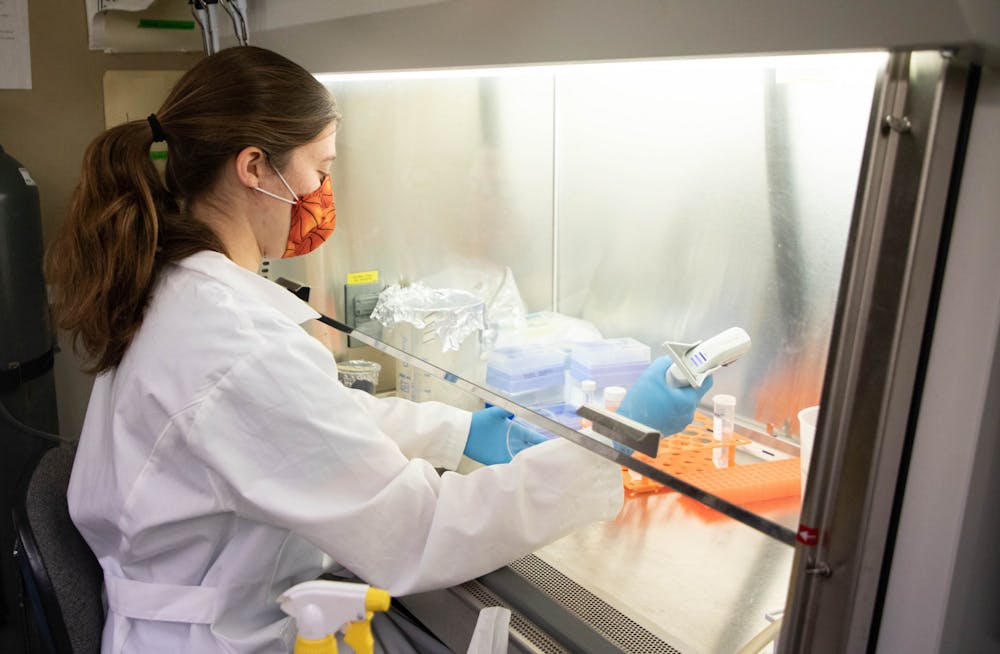

Many nights, Siara Sandwith can be found descending a flight of stairs to the basement of Cooper Science Building to finish her experiments in her 12-by-24-foot, 65-degree lab.

“It became alarming to me when I went to the lab at 3 a.m., and a night-shift custodial staff member told her co-workers that she already knew which lab I was headed to,” Sandwith said. “My lab partner normally goes to the lab with me. When she can’t, I have a wonderful, selfless roommate who comes with me. There have been nights where my other friends tag along and do homework or dance choreography in the hallway. These are some of my favorite lab memories, and I’m lucky to have such a great support system.”

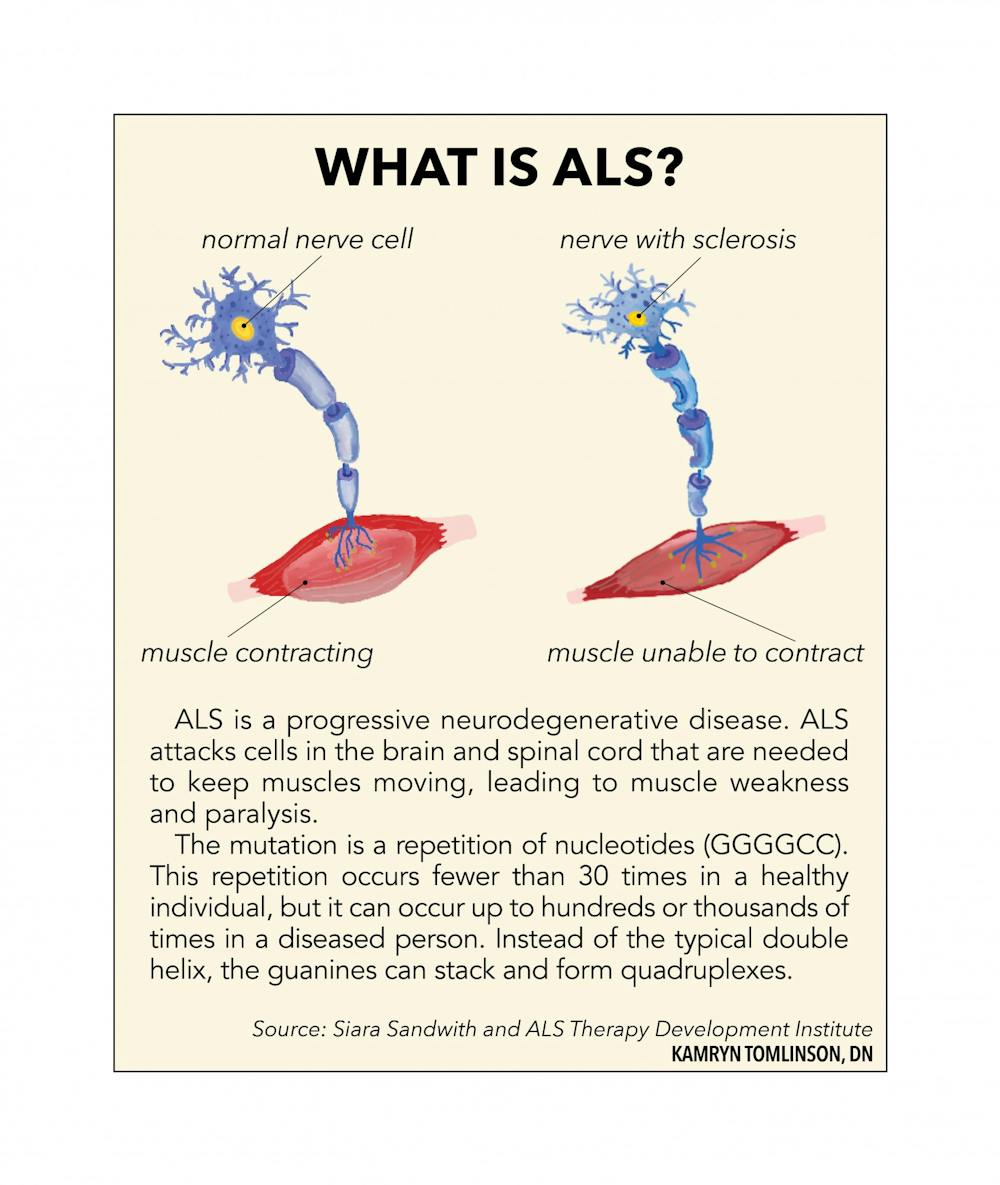

As a senior biology major and undergraduate research assistant, Sandwith conducts experiments to examine the genetic mutations linked to the neurodegenerative disease amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, commonly known as ALS or Lou Gehrig’s disease.

“Our lab is specifically interested in studying a protein called G4R1, which unwinds G-quadruplexes,” Sandwith said. “You can think of it as untying a knot. I use various biochemical assays to observe how G4R1 interacts with this gene mutation to better understand the disease.”

A personal connection

Before her freshman year, Sandwith’s uncle died from frontotemporal dementia (FTD), a disease that affects the temporal and frontal lobes of the brain and causes changes in behavior, personality and language. Because FTD is linked to the mutation Sandwith researches in her lab, she said, this connection makes her research all the more meaningful.

She and her uncle bonded over their love for books, Sandwith said, and she keeps the books he gifted her as keepsakes. The most important impact her uncle had on her life, she said, was the great relationship he had with her father. Sandwith's dad grew up with three sisters, an older mother and a disabled father, and her uncle was one of the prominent male figures in her dad’s life.

“[My uncle] was the one who taught my dad how to fish, shoot, boat, camp, race motorbikes and most importantly, all the torture tactics to bully your siblings,” Sandwith said. “My dad then shared these things with me and my three older brothers.”

Siara Sandwith uses the microscope to evaluate if the cells are growing healthy Sept. 21, 2020, at the Cooper Physical Science Building. Sandwith also uses the microscope to check if the dish of cells is becoming too dense. Sumayyah Muhammad, DN

Because her uncle’s progression was quick, Sandwith said she didn’t see most of the dramatic changes in his personality. However, Sandwith remembers when she was leaving a restaurant with him one time, his behavior was “very uncharacteristic and almost appalling.”

“This behavior was mild compared to the things he did toward the end of his life,” Sandwith said. “Based on stories I have heard from my family, the descriptions did not match the man I knew. The change this disease can cause is truly shocking and sad to witness.”

In the lab

Sandwith’s experiments can be unpredictable, she said, so she never has a typical day in the lab, and her agenda changes daily based on the results of her previous experiments.

“Sometimes, I can leave the lab by 3 in the afternoon, whereas other times, I don’t leave until 7 or 8 at night,” Sandwith said. “If I am waiting on an incubation — when samples are cooked at a specific temperature and time — and I am not actively at the bench, then I am working on homework at a table outside of the lab, preparing data presentations for a lab meeting or I am doing lab dishes. Longer incubation allows me to leave for lunch or attend club meetings.”

Sandwith’s interest in cellular and molecular biology began when she was a freshman in high school. When her biology class studied its textbook’s molecular genetics chapter, Sandwith said, she was astounded and realized the specific interactions and organizations of cells seemed beautiful to her.

“Up until [that] point, I had been going through the motions of my faith,” Sandwith said. “I hadn’t really questioned or sought answers to whether God exists or not. But, after learning about molecular genetics, I was thoroughly convinced that something or someone had to exist to create something so complex, so beautiful, so fragile. By studying cell and molecular biology, I believe that I am ultimately seeking truth and beauty.”

Philip Smaldino, assistant cell biology professor at Ball State and Sandwith’s mentor, recruited Sandwith as a freshman to join his research lab in the spring of 2018. Based on her impressive GPA and positive, professional interview, Smaldino said, Sandwith was the first freshman he accepted into his lab.

“I have been utterly impressed with Siara since day one,” Smaldino said. “I was impressed with her ability as a freshman to read and comprehend primary literature. I noticed right away that Siara is honest, genuine, firm in her convictions and a natural leader.

“[Sandwith’s] devotion and commitment to the lab has motivated me on numerous occasions to push myself a little further. When a student goes above and beyond, it nudges the mentor to do the same.”

Along with working part time at Ball State Memorial Hospital and maintaining a near 4.0 GPA, Sandwith spends 15 to 30 hours a week in Smaldino’s lab. Smaldino said it took nearly 18 months — including working almost full time during the summer months — of troubleshooting her experiments for Sandwith to obtain her first piece of publishable data.

“Science has taught me a whole new level of mental toughness,” Sandwith said. “In research, you encounter failure much more frequently than success. You learn to accept that failure is normal. When you produce good results, it is all the more rewarding.”

A Goldwater Scholar

In late March, Sandwith was awarded a Goldwater Scholarship, the nation’s most prestigious scholarship for undergraduate students pursuing research-based careers in the STEM fields. Sandwith was the 12th Ball State student to receive this $7,500 scholarship.

Sandwith said she learned about the Goldwater application after speaking with Barb Stedman, director of National and International Scholarships and Honors Fellows at Ball State, during her freshman year. Given her research experience in Smaldino’s lab, Stedman said, she believed Sandwith would make an excellent Goldwater applicant.

“Siara’s an excellent writer, but she’s not very good at bragging about herself because she takes her many talents and accomplishments for granted,” Stedman said. “My biggest challenge [helping Sandwith with her Goldwater application] was helping her see that her path to becoming a molecular biology researcher is a fascinating story worth telling. Siara is great fun to work with. She’s willing to put in the hard work needed for any scholarship application, and she has a dry sense of humor that I really appreciate.”

The day she would find out if she was a Goldwater Scholar, Sandwith said, she was anxiously waiting by her computer and washing dishes to keep herself busy. After feeling blessed from what she had accomplished that school year, Sandwith said, she was suspicious of how well things were going for her.

“My paper was accepted for publication, I won an internal grant, my experiments were going extremely well and I had several summer internship offers,” Sandwith said. “[I thought], ‘Surely I won’t win the Goldwater too.’ But I had Dr. Smaldino and Dr. Stedman in my corner, so none of this should have come as a surprise. I am extremely grateful for all the help and support they have given me.”

After she graduates from Ball State in May 2021, Sandwith said, she hopes to attend the University of Michigan and to earn a Ph.D. in cell and molecular biology or biological chemistry.

“Siara is well-situated to succeed in whatever vocation that she is called to,” Smaldino said. “She is realistic and resilient. I have no doubt that Siara’s future will be bright.”

Contact Sumayyah Muhammad with comments at smuhammad3@bsu.edu or on Twitter @sumayyah0114.