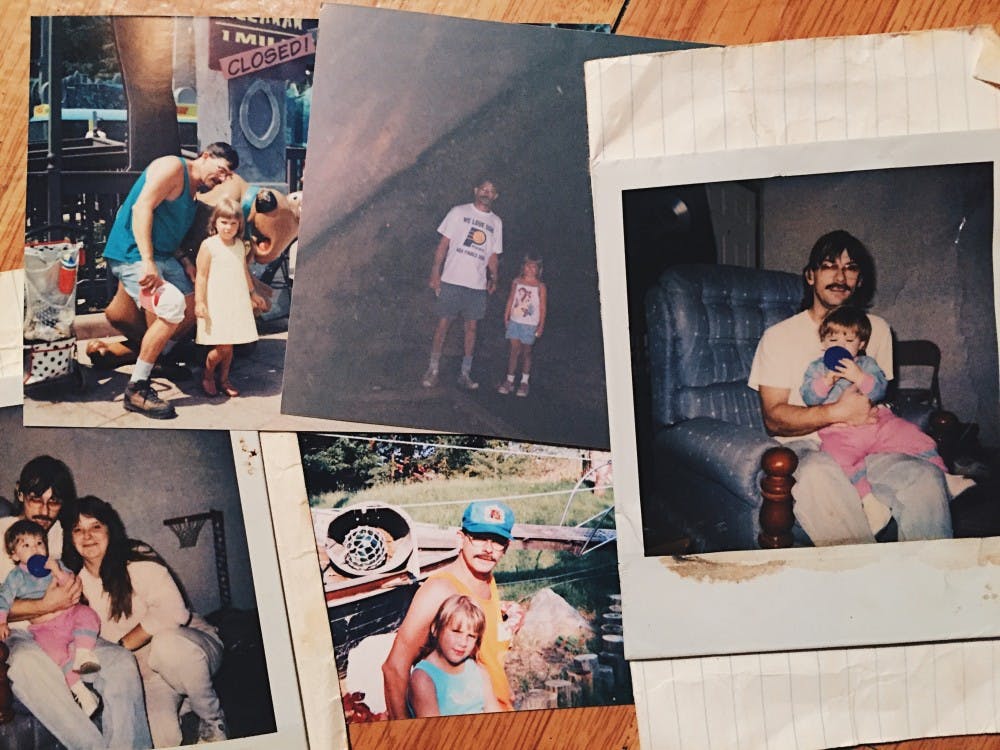

The loss of a father, husband, brother and friend

This started when I couldn't sleep the first night we were in the hospital and decided to take a few photos because the lighting was interesting. From there, I realized I wanted to document whatever the outcome may be of my father's illness.

I believe in my heart he would be okay with this because he knew how important photography is to me. He always wanted to hear about what I was taking photos of and if I had been to the latest game or concert.

I’d like to think the opportunity I had to be by my dad’s side, holding his hand, as he took his last breath is a unique one.

Unique because it was the last time we would be a whole family. Unique because I was able to watch how a disease can affect a person and the people around them until the very end.

Unique because he was.

I understand he is gone, but I have hardly begun to accept all he will miss.

All photos were taken with an iPhone 6 and edited on the VSCO mobile app, using only the HB2 preset.

WARNING: The following may contain graphic images or sensitive material.

Dec. 24, 2016 — It was the first night we spent in the hospital. I say spent because I slept all of 30 minutes. I was more concerned about receiving an update on my father and about our stuff being stolen. So, I reassured my mother she could sleep through the night and played relaxing music to help her.

He was resting when we visited him that morning. We were told the internal bleeding hadn't stopped, but the bleeding in his head had.

He had been given five bags of blood in less than 24 hours of being admitted to the hospital and would be given three more later in the day.

My father had become depressed, again. After losing his job earlier in the year and struggling to find another, he began to feel more useless. It was around this time he started to become more sick.

Dec. 27, 2016 — We found a more secluded room to call our home for the next week. Many people came and went, but my mother found people to talk to here and there. One lady in particular, whose husband suffered from a heart attack, was a constant friend of hers. When they weren't chatting, or on Facebook, my mother was on her phone answering questions back-to-back from concerned friends and family.

Dec. 27, 2016 — We had a routine for when we would go see him: early morning (8 a.m.), early afternoon (1 p.m.), late afternoon (4 p.m.), evening (8:45 p.m.) and late night (12 a.m.). The routine that hit me the hardest was my mother kissing her hand and pressing it his forehead, then stroking his hair back. She would whisper, "I love you," "Goodnight" or "Get better" before walking out of the room for the night.

Dec. 28, 2016 — There were small improvements—like a roller coaster, it had its ups and downs. The rotation of 10 types of medication seemed to be working.

Little did we know my father's drop in blood pressure at once a day is a sign of liver disease—a symptom he has had since my parents were married in 1982. A doctor reassured my guilt-stricken mother they would not have known the symptoms 34 years ago.

Dec. 28, 2016 — The day nurse called it a "stable day."

It had been five days, four of which he had been on a breathing machine. High ammonia levels mixed with pain medication caused him to be in a coma-like state for almost a week. My father was not a man of minor responses; he always had something to say. Nurses said he was "in good spirits" when my father had arrived, and he was making jokes about leaving. That all changed within a couple of days.

The day before, we had learned his stomach was processing foods incorrectly, and they had to give him a direct line to his small intestine.

Dec. 30, 2016 — One thing my mother looked forward to in the waiting room was a good sunset. While looking out, she would point out buildings and make small talk about his progress. We talked about how it would be months before he was better, and how she was prepared to stay in the hospital with him until then. Visions of her stroking his hair and whispering "I'm here, okay. We're going to fight this together," at the end of the night filled my head.

I never told her, but it was then I decided I would come down every weekend until he was better.

Dec. 30, 2016 — My mother became obsessed with every vital sign and watching my father's swelling in his hands and feet. Any sign of the swelling going down was a good one to her.

The day before, the lead doctor informed us there were a lot of unknowns in his case and the prognosis wasn't good. His head trauma, his stomach, his kidneys and his liver, which was severely damaged, were slowly getting better. Then the doctor asked it: If his heart were to stop, what did she want them to do? "I can't lose him. He's all I have."

Dec. 31, 2016 — Not many things had changed for a few days. Drops here and there in his electrolytes. A steady amount of stool. No more blood.

As the days went on, I began to hear her say more and more she was praying. When she goes out to smoke a cigarette, when she goes to walk, when she tries to fall asleep, she prays. Ever since I was a child, neither of my parents had expressed any kind of religious view. It was different in the hospital. She told him at least once a day that people were praying for him. She seemed optimistic with prayers on her side.

Dec. 31, 2016 — Every morning felt the same, and the days began to blur together. We hardly realized it was New Year's Eve until watching the news later in the evening.

I could tell the lack of sleep and monotonous days were beginning to catch up with her. She seemed more weary. I wondered how she would survive the long days of nothing while I was in school. Who would make sure she ate and went to sleep? I tried to plan out the next four months and how they would be spent at the hospital.

Jan. 1, 2017 — His platelet count dropped into the 40,000s that morning, so he received more in the afternoon. His ammonia level had gone from 100 to 140, as well. They decided to do a chest X-ray, finding pneumonia. Shortly after, a doctor told us his chances of fully recovering and being the same as before were very low.

The night before, they noticed some discolorations in his stomach pump and stool; they believed it was blood.

Jan. 2, 2017 — The lead doctor had told us earlier his liver was basically non-functioning. His kidneys had taken a turn for the worse. They said he was in a coma; his liver had not processed the ammonia, which kills brain cells and causes swelling in the extremities. They were expecting lung failure soon—did we want to make him more comfortable? Take him off the breathing tube and let the process be more natural.

They didn't think the medicine was going to work anymore.

I knew he would be gone by the end of the day, and I think my mother did, too. My brothers, uncle, grandfather, great aunt and my brother's girlfriend made the trip to say goodbye.

Jan. 2, 2017 — "Wake up," she pleaded while shaking his hand, tears streaming down her face as my oldest brother held her. It was the first time I saw her cry during those 10 days.

The hardest part for me: watching my mother beg the love of her life not to leave her.

I tried to think of my favorite story from when they started dating in 1980. He had given her a bracelet with his name on it. When he went to take the bracelet back, she bit his hand, and they had been together ever since. She was going to allow him to leave her life then, but she wasn't ready to accept it.

Jan. 2, 2017 — The room was full of sniffles and tears, but my uncle stood out. I had never seen him like this. I had never seen my grandfather like this.

It's a weird and indescribable feeling watching them. A true sign of becoming older.

And I finally accepted that it was okay for me to cry.

Jan. 3, 2017 — At 1:48 a.m., he took his last breath. I'll never forget the colors of his face and how cold his body felt afterward.

At 3:30 a.m., we arrived at a hotel. I didn't sleep but felt exhausted.

At 8:30 a.m., everyone woke up to eat. We talked about all the things he used to cook for breakfast.

At 1:45 p.m., we were home. I remembered I had bought them two presents. On Christmas, my mom said, "We'll open them when your dad gets better." Seeing the large present addressed to him made me realize all the little moments I would miss. He wouldn't laugh at my handmade card. He wouldn't be able to wear The Daily News crewneck, something I knew he would be proud to wear. He wouldn't make jokes about the back scratcher, either.

Jan. 3, 2017 – Nearly 14 hours later, we were discussing funeral arrangements. As a child, you never really think about planning your parent's funeral or filling out a death certificate and knowing how many you'll need.

When it came to choosing an urn, it hit me all over again. We picked out a nice wooden one, because he was a woodworker, for my mother. My brothers and I picked out token urns to always keep.

My mother had talked about various places to spread some of his ashes, but by the end of the meeting, she had decided. Some would be spread by the twins, who were born prematurely and did not make it. When it’s her time, she said she wants her ashes spread on the other side of the twins’ grave.

Boxes and boxes of old items. His favorite book in high school, Lord of the Rings; a broken razor; any card that had his name on it; guitar picks; a confiscated slingshot; too many hats. We had to go through it all.

The first thing to be divided was old band T-shirts—some were too tattered to be worn. Then we moved onto his regular clothing and other items, each with a memory or purpose.

While we were going through it all, my mother would say to me once or twice, "You know Bre, I think he knew he was dying."

Jan. 4, 2017 — After going through his possessions in the bedroom, my brothers started cleaning my childhood room. He had claimed it as his own for storage, and for his alcohol.

Nearly 10 empty tequila bottles were thrown away as well as a case of beer and any other leftover alcohol. There was another room across the hall waiting to be cleaned.

He wore a gray suit, maroon dress shirt, a faded blue Led Zeppelin t-shirt and his favorite pair of orange slippers. My mother wore maroon and gray. In his hand, he's holding a guitar pick and the Ball State hat I bought him. He had decided it would be the only hat he would wear until I graduated.

My brothers decided to ask friends to wear old band T-shirts, and they passed out guitar picks as a keepsake. To keep with the theme of classic rock ‘n' roll, we put his guitars and guitar cases on display. His service began with Shine On You Crazy Diamond and ended with Wish You Were Here, both by Pink Floyd.

Jan. 7, 2017 — It was the last night before I left to come back to college, and I wondered if my mother would be okay in the house by herself. I think she knew because she would mention she has "the animals" (two dogs and three cats) to keep her company.

That day, she had decided she would buy a new couch they had planned on getting. Soon, it would join the six bouquets, two baskets of flowers, one spray, one figurine and one blanket in the house.

During the days before I left for Muncie, my mother would occasionally say: "He's gone. He's actually gone, Bre."

I never had a response.

How could I respond?

Nothing prepares you for the death of your biggest supporter.

If you, or anyone you know, is suffering from depression or alcoholism, please do not hesitate to reach out to them, and direct them to help.

Suicide Hotline: 800-784-2433

Crisis Call Center: 800-273-8255

Alcoholics Hotline: (866) 247-1603