When Chief Jim Duckham speaks, there is no mistaking his origins. Growing up in Long Island, New York, there wouldn't be any way to hide his accent.

In the shadow of the Statue of Liberty, Duckham cheered relentlessly for his beloved Yankees, and he can drive you to a place in Queens where the pizza is typically New York-style: thin and hot.

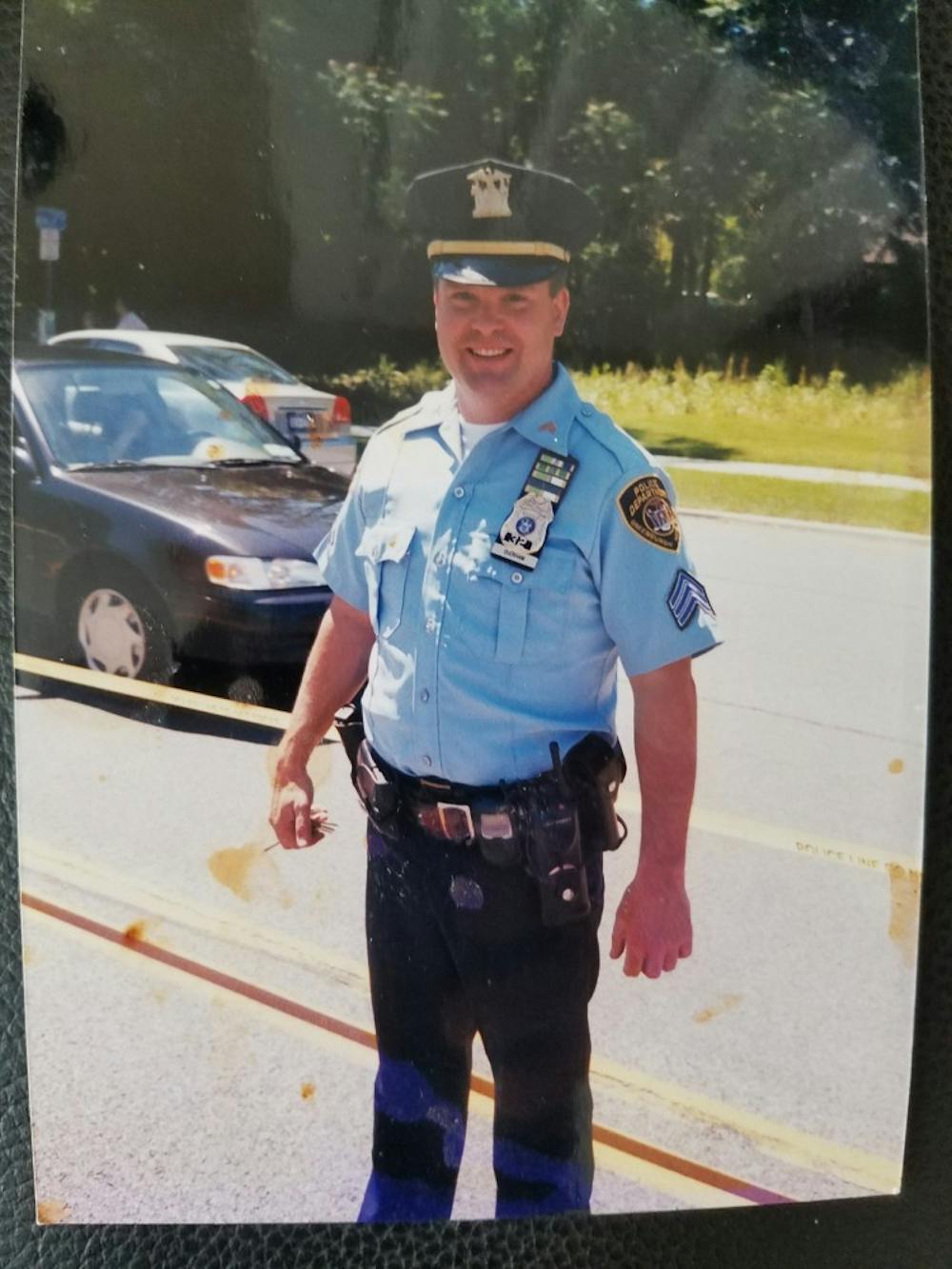

Life as a patrol sergeant in Greenburgh, New York, was pretty much what Duckham expected it would be.

Until 17 years ago — Sept. 11, 2001 — Duckham, Ball State’s chief of police and director of public safety, like many other officers working in New York at the time, went to work on a day that would turn out to be one many Americans will never forget.

The United States was attacked on its own soil, as two jets crashed into the World Trade Center and one jet flew into the Pentagon in Washington, D.C. A fourth plane that was intended for the Washington, D.C., area was instead deliberately crashed into a field in Pennsylvania, after that plane’s passengers overpowered hijackers who had taken control of the flight.

“I remember it was a beautiful day,” Duckham said. “Just the weather, I don’t know if you’ve seen any of the footage ... just crystal clear.”

Duckham, who was 37 years old at the time, was one of 115 officers in the Greenburgh department. After reporting to work in the town with a population of more than 80,000, Duckham fell into his normal routine. He completed roll call, gave assignments, assigned vehicles and sent the officers on their way.

Chief Jim Duckham during his time with the Greenburgh Police in New York City. Duckham was working as a patrol sergeant for the department when the World Trade Center was attacked by terrorists Tuesday, Sept. 11, 2001. Jim Duckham, Photo Provided

“So it was kind of funny, I remember I was driving by town hall, it was just a beautiful day and I was listening to WPLJ. We didn’t have satellite radio in our police cars. That particular radio station was a current music type of thing,” Duckham said.

He was enjoying it, he said, though that wouldn’t be the case for long.

The program abruptly stopped and informed its audience that a plane had hit the World Trade Center. Duckham assumed it was a smaller plane, not a jet and tuned in, hoping for more information.

“I thought, ‘Well that’s odd, how do you crash a plane into the World Trade Center?’” Duckham said.

By the time Duckham got back to the police station, the chief of police and captains had already arrived.

“The TV was packed with people [crowded around] and everyone had started watching,” Duckham said. “I drove down [through] the south end of our town. We had three paid fire departments ... and by the time I got there, all the fire engines were gone.

“I sat down for a minute and watched the coverage. It was pretty chaotic, really nobody knew at the time what was happening.”

As he watched the towers collapse, he wondered how anyone could survive.

Duckham, like many workers in the emergency service agencies, went into "save mode," but at that moment, nobody knew what that would entail. He said a lot of the emergency responders who went to help weren’t actually called in, but self-dispatched to the scene.

“I don’t think anybody really understood the significance of that,” he said. “In policing and firefighting you’re like, ‘Oh, we’re gonna go save people.’ That was our mentality.”

But Duckham and others who have first-hand memories of that day said the chaos of the situation made that self-dispatching more unintentionally problematic than helpful. That was driven in part by the sheer magnitude and unexpected horror of this type of emergency. In short, literally nothing like this had ever happened on American soil.

Greg Hess, a former member of the Federal Emergency Management Agency’s (FEMA) Indiana Task Force 1, was sent in with the group 16 hours after the second plane hit the second tower. Task Forces in FEMA are specialized rescue units that are scattered across the country in case of a large disaster or emergency.

“You have so many people that are trying to help and want to help,” Hess said. “But you have to be able to document who they are and where they are in the event that, God forbid, they get hurt or worse.”

This, Hess said, made the initial response effort look like “a bunch of ants running around.”

Thousands of first responders were either dispatched, or self-responded, to attempt to secure the area, search for civilians and make rescue attempts.

Duckham’s unit was halted a few miles back from the site, awaiting commands from superiors who had never dealt with this type of situation.

“Nobody really knew what to do with everybody,” Duckham said.

Before Duckham left to drive toward Manhattan, he broke his usual routine by making a call to his wife.

“I remember telling her, ‘Hey, we are going down there [Manhattan]’ and typical things, and ‘Hey be careful.’ Silly stuff like that,” Duckham said.

Duckham’s unit traveled down a 5-mile stretch of highway to get to the site, though he passed no civilian cars on the way.

“All you could see were police agencies coming out of Westchester,” Duckham said. “It was the most eerie thing I can remember, because I had grown up in Long Island, and I had never seen no traffic.”

Upon arrival, Duckham and the other Greenburgh officers weren’t given any instructions except to wait. It was then that he experienced a moment that still sticks with him today.

Duckham, along with his fellow officers, had been stationary for a few hours. They sent the rookies out in search for food, not realizing how bad Ground Zero had become. It was then that a rescue van full of firefighters came out of the site.

“This truck goes by … there were guys that were sitting on it. One guy was sitting on the step and he was covered in the soot. And these guys didn’t say anything, and you could just see the devastation in their face,” Duckham said.

Suddenly, the officers that were in search of food while waiting for orders fell silent.

“That’s how, until the day I die, I’ll remember that moment,” Duckham said.

Hess, who was at Ground Zero, said the scene was almost indescribable.

“Absolutely overwhelming,” he said. “The debris pile was seven stories tall, spread out over 16 acres and we had seen the smoke from the pile, and we were about 30 miles out from New York City.”

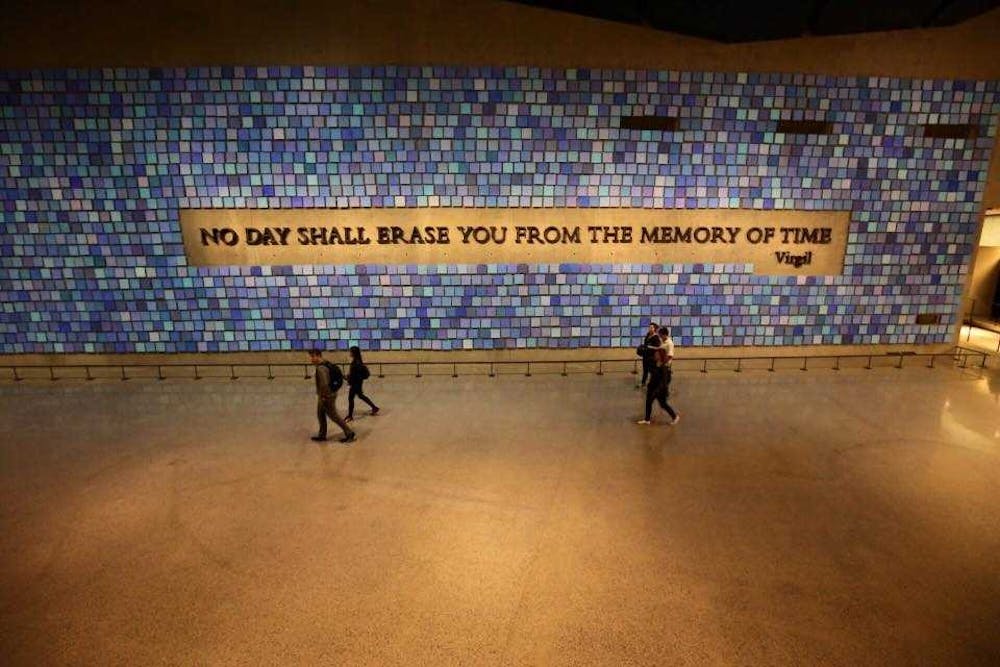

Thirteen years after the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks, the new One World Trade Center building opened to the public. Considered to be the tallest building in the Northern Hemisphere, the tower is conversationally known as Freedom Tower. Lisa Renze-Rhodes, Photo Provided

Yuval Neria, a professor at Columbia University, studied the correlation between working at Ground Zero and post-traumatic stress disorder. He concluded that even being close to the site of the attacks would result in experiencing PTSD.

“Indirect exposure to [the] 9/11 attacks was found to have detrimental long-term consequences. Not for all but for many. In particular among those who lost family members, friends and colleagues. The impact can be resulted in long term PTSD and complicated grief,” Neria said in an email.

While Duckham’s unit wasn’t at Ground Zero, it still felt its effects. Later in the evening, it was moved under a bridge to guide traffic, and while they wore respirator masks, they could taste the seemingly endless soot.

“I’m not a scientist, and I’m not saying I had foreshadowed that guys would get cancer, but I knew enough through being around emergency management that breathing this stuff in can’t be good,” Duckham said.

Hess’ unit saw similar issues. He said there were 63 members on his task force and out of those, 26 have gotten sick and six have died from the Ground Zero exposure. In 2007, Hess himself was diagnosed with Stage 3A colon cancer, though he has been in remission since 2008.

One of the main reasons cancer is so common is the over exposure to soot, a byproduct created when something isn’t completely burned. According to the National Cancer Institute, the powder inside soot many carcinogens, such as arsenic, cadmium and chromium.

“We went from being rescuers [to] six years later, I became a victim,” Hess said. “When you see all these people that are dying, and getting sick, it’s just, you know, it’s unfortunate that the death toll for 9/11 is going to continue to grow, and grow and grow.”

Duckham said he still wonders if he had stayed on as a New York City cop if he would have worked Ground Zero after that day.

“I would never want to give the impression that I did anything other than basically traffic,” Duckham said.

“I’m certainly grateful that I didn’t lose my life, and that I hadn’t been working [Ground Zero] that day, in the sense of being a police officer that was there,” Duckham said. “Think about it, 300 plus firefighters, 50 some cops, who really just went to work that day.”

Contact Charles Melton with comments at cwmelton@bsu.edu.