Editor's note: An earlier version of the graphic incorrectly labeled Fuelling's meniscus tear as a microfracture. The graphic has been updated.

When Alex Fuelling’s collegiate volleyball career ended, the score was 11-7 in the second round of the Mid-American Conference women’s volleyball tournament.

The senior outside hitter jumped up to hit a ball, and she landed not on the floor — as she had practiced so many times — but on her teammate’s foot.

She knew something was wrong — she had felt her knee pop out and go completely sideways, then go back in. Then she was down on the ground.

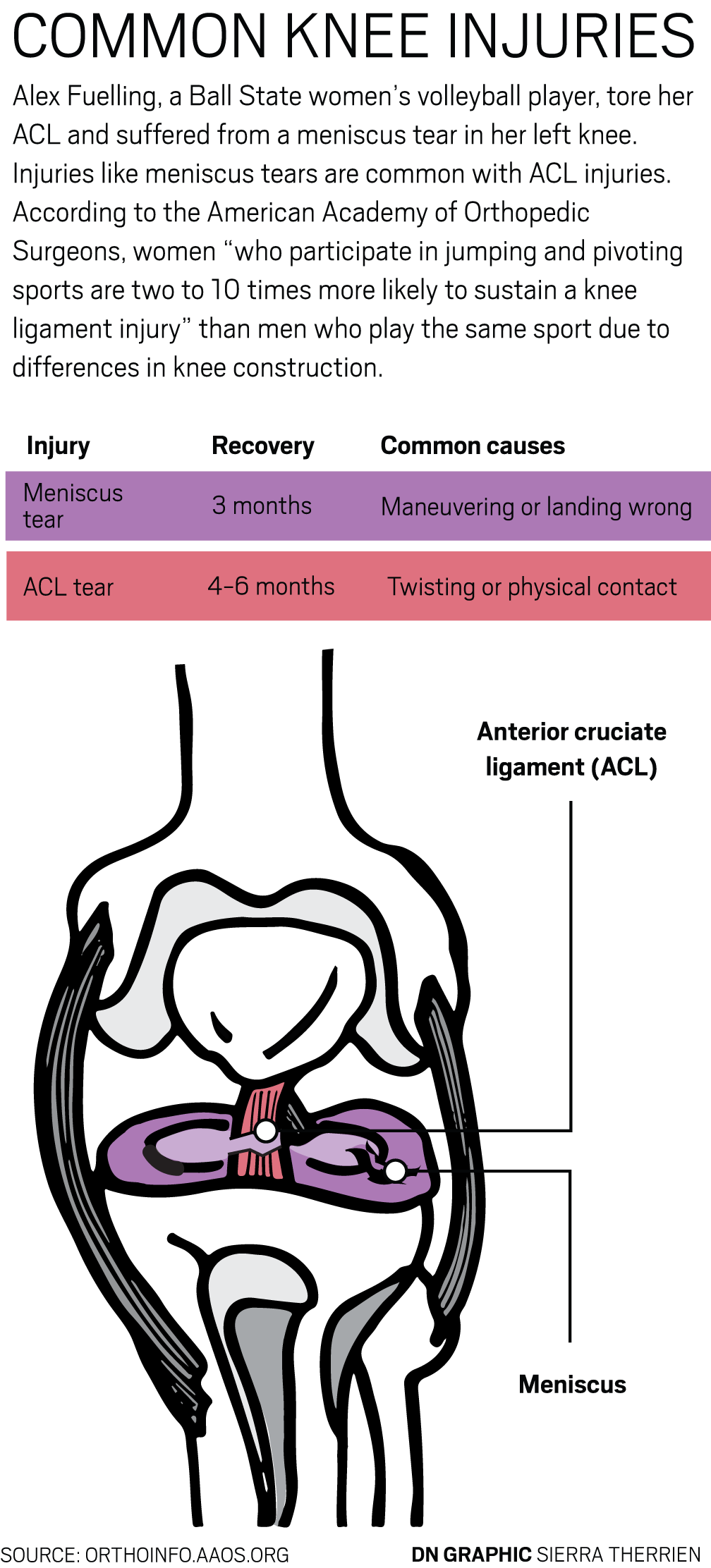

The impact tore Fuelling’s ACL and meniscus, and she was forced out of the game — and the last moments of her collegiate career.

“Knowing that that was my last game … was really frustrating, but once I sat down and thought about it, I guess I was glad that it happened when it did and not earlier in the season,” Fuelling said. “I was at least able to complete the season — it just happened at the worst time.”

Sports injuries are often unavoidable for athletes. From 1988 to 2004, the National Athletic Trainers’ Association reported anywhere from 14 to 18 percent of athletes were injured during games or practice. And that doesn’t even include the injuries suffered outside of the sport.

But often the physical aspects of the injury aren’t the worst part — it’s the psychological impact that can hurt athletes the most.

Physical readiness to get back into the game after an injury can be more easily determined by athletic trainers, but psychological readiness is harder to detect, said Lindsey Blom, an associate professor of sport and exercise psychology.

Many of these injured athletes end up playing through the pain, because they’re unwilling to stay out of the game for longer than they absolutely have to.

“Athletes may not be honest about [their psychological readiness],” Blom said. “If they’re not both ready to go, then there’s definitely a better chance for reinjury or not as good of a performance.”

And the desire that most injured athletes have to get back into the sport can slow progress down or lead to reinjury if it isn’t controlled, she said.

Athletes often go through five stages of grief after an injury, Blom said.

- Denial – where an athlete will play through the game or practice when they’re injured, but won’t accept it. They also may not realize the extent of their injury, and some of the pain may not be evident.

- Anger – where they may get frustrated and get into the “why is this happening to me” mentality

- Bargaining – players may do anything they can to get back into the game, even trying to convince their coach to let them play more as long as they do their rehab

- Sadness – athletes may withdraw from their teammates, coaches and friends

- Acceptance – the stage the athlete needs to be in to be able to move on and heal properly

When Fuelling got hurt at the MAC tournament, she was able to get up off the court and walk to the bench. It wasn’t until later that night when the adrenaline from the injury wore off and she woke up in pain and realized the full extent of her injury.

“I was able to walk off the court by myself, that’s why I was crossing my fingers I could go back in,” Fuelling said.

But she said her trainer was stern in his ways, and wasn’t going to let her go back into the game no matter how much she begged.

EMOTIONAL HARDSHIPS

For Fuelling, the worst part of her injury wasn’t the pain that would cause her to wake up crying some nights, but the realization that she didn’t have anything to come back to.

Fuelling had made that same jump countless times in her career. But with one wrong fall, her college career was over.

“It did take me a while to really be able to understand what was going on and just be thankful for the opportunity that I had and feel lucky that it didn’t happen earlier in the season,” Fuelling said.

One positive from her injury happening at the end of the season was there wasn’t a rush for Fuelling to get back into the game.

She had surgery over Winter Break, allowing her time to sit at home and recover. She could barely walk and had to keep her knee completely straight so the meniscus could heal.

Unfortunately, this wasn’t her first time around playing the recovery game.

Earlier in her senior season, she sustained a microfracture in the cartilage of her left knee, which kept her out for three weeks during the team’s preseason.

“It took me a while to get back into it, just because I was really hesitant on something else happening,” Fuelling said.

Getting back into the game was a matter of finding the confidence she had before she got injured, and not worrying what could happen to her knee — and just focusing on playing.

“It’s going to hurt — that’s part of having an injury,” she said. “I just had to find confidence in my knee and in myself to get back to where I was before.”

Jessica Rager, a doctoral assistant in the athletic training program, said this was a common occurrence with injured athletes.

“Think about an athlete’s confidence in their own ability, as well as the confidence in that body part,” Rager said. “If I have a knee injury and I’m a basketball player, me having those first practices and first game, I’m thinking, ‘Do I trust my knee, is my knee going to give out on me again?’ These are real questions athletes have.”

PLAYING THROUGH THE PAIN

Junior tennis player Andrew Stutz hadn’t committed to play in college when he fractured his leg.

At a birthday party at SkyZone his senior year of high school, Stutz was jumping up and down in the dodgeball area, not focusing on anything. He threw a ball and jumped up, and his left leg came down on the trampoline and his right hit a platform in between the trampolines and snapped.

He couldn’t walk for four and a half months, and many college coaches he was talking to backed out. But head coach Bill Richards believed in him and still signed him.

He made it through his first two years of college with the help of a lot of pain killers and encouragement from teammates. Stutz said he didn’t consider quitting after breaking his leg — he knew he still wanted to play in college.

After he broke his leg, doctors put two plates and 16 screws into his leg, and he ended up playing in a lot of pain throughout his freshman season.

“Tennis is so movement-based, and I could only move well for about an hour,” Stutz said. “It’s hard to get confidence when you know you can’t play a whole match at your best.”

He was playing entire matches, and because his injury was on bone rather than muscle, the physical therapy couldn’t help much.

He worked to strengthen every part of his right leg, as well as his left since he was using it more than usual.

“I kind of just had to deal with it — there was a lot of Vicodin and just smiling through the pain,” he said.

For Stutz, it was especially hard since he was coming into college injured. The transition from high school to college is already difficult for athletes, and adding an injury to the mix made it worse.

The workload is harder, and the added freedoms of college can be challenging for a lot of athletes. In addition, the sadness, isolation and time and stress management an athlete faces during the transition can mimic what injured athletes face, according to an NCAA study.

But Stutz’s teammates and Richards were able to help him through it. They knew he needed more support to get through matches, so they would cheer for him a little harder.

The plates and screws were taken out the summer after his freshman year, and his leg doesn’t hurt him anymore. But Stutz said he still gets nervous sometimes that his leg won’t hold up.

“I think there’s an inherent mental thing about it,” he said. “I’m getting better, but whenever I move to the right, there’s still a little bit of that fear [that I’ll re-injure it].”

FORCED TO QUIT

While Stutz was able to fight through his injury and keep his career going, former swimmer and junior business and biology major Amanda Baskfield’s injury forced her to make a tough decision.

A few weeks into her freshman year, she felt a sharp pain in her shoulder near the end of one practice, and she later found she had torn her left bicep’s tendon off of her rotator cuff.

Baskfield couldn’t lift her arm very high and was forced to only kick and do leg workouts during practices. She went to rehab three times a week to try to strengthen her shoulder, but she ended up needing surgery during Winter Break.

She was out of the pool and practice after surgery, fully immersed in rehab to get her shoulder back to where it needed to be.

Baskfield was planning on trying to continue to swim after surgery, but during Spring Break she talked with her mom, friends and former coach about potentially quitting.

The X-rays and MRIs on her shoulder showed it would be probable that she’d tear it again within the next year, she said.

So she made the hard decision to put her health first and quit.

Baskfield had been swimming for 10 years, and it was a huge part of her life. She went to see a sports psychologist after she quit because she didn’t know what to do with herself.

“All I knew was swimming,” she said. “My schedule was revolving around practice and meets, and I had to figure out what to do. I think I would have gone into a huge depression slump if it wasn’t for [the sports psychologist.]”

Baskfield didn’t realize how much anxiety she had without swimming, but once she lost her stress relief and way to cope with daily life, it all came out. It made losing the sport that much harder.

By focusing on the mental aspect of the game, sports psychologists can help athletes improve during games or practice, get over mental blocks and work through any issues they may be having.

But they can help athletes with more than just improving their game. After an injury, or after quitting due to an injury in Baskfield’s case, they can help athletes tolerate pain and adjust to not playing anymore, according to the American Psychological Association.

Ball State offers sports psychologists for athletes to meet with if they choose to, and some coaches have the psychologists come in to work with the whole team.

Rager, the athletic training student, said the psychological impact after a big injury can be huge when it comes to the rehab process.

“You identify as a member of the team, and you have this injury now and your world has completely been flipped upside down,” Rager said.

Baskfield immersed herself into her major to fill the space in her life that was left after she quit. But even two years later, she still misses it, and she still deals with the pain from her injuries.

“I had a lot of nerve damage, and it’s stuff I still deal with today,” Baskfield said. “In the end, it just ended up being a better fit for me healthwise that I wouldn’t continue.”